THE STRAWBERRY CONSPIRACY ( The Plantsman, Prequel to The Conquest of Dough.

A Satirical Tale of Artificial Scarcity and Natural Abundance In the Style of Will Cuppy

THE PLANTSMAN: PRECOGNITIVE POSTCARDS

A Prologue in Three Chapters

Being Postcards from a Journey to the Unknown, Written Before the Journey Began

PROLOGUE: THE TICKET PURCHASE

In Which One Realizes the Train Has Already Left the Station

I started writing this because I realized I was locked into a series of events for which I would be subject to the results, but over which I would neither be consulted nor considered¹. The realization was quite comforting, in the way that discovering you're already falling can be comforting—at least the uncertainty is over².

We're all precogs now³. Not in the Philip K. Dick sense of seeing the future, but in the more mundane sense of recognizing patterns that haven't quite finished repeating themselves⁴. The postcards I'm writing are from a journey that began before I bought the ticket, to destinations that were selected before I knew I was traveling⁵.

This blog represents a purchase—mentally—for my ticket for the ride⁶. A journey I was determined to understand, enjoy, and share some postcards with myself and others who might be interested, having realized they too may be taking the same train⁷. As with all postcards, some are written more thoughtfully, others are scribbles just checking in or marking out places to revisit⁸.

The train, I've discovered, runs on a peculiar schedule⁹. It stops at stations that don't appear on any official map: Artificial Scarcity Junction, Planned Obsolescence Central, and the sprawling terminus of Systematic Abundance Suppression¹⁰. The conductors speak in languages that sound like economics but mean something entirely different¹¹.

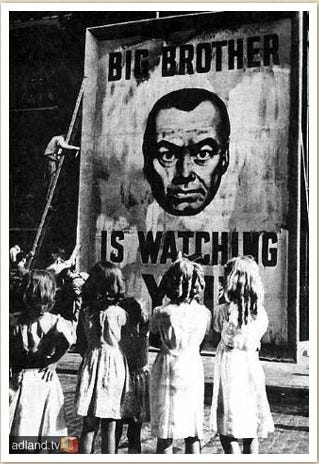

And 6 billion pairs of Eyes stared back and didn't like what they saw.

The concept of the thin blue line, the tipping point, and the fragility of the

illusion of power had been recognised. We the 99%, the people are the

system.

The Plantsman, 2013 ( R. G . Lewis)

AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION

Being a Necessary Explanation of How This Work Came to Be Written, and Why

The reader may wonder how a man who died in 1949 came to write about events that occurred in the early 21st century¹. The explanation is simple: I didn't. This work was discovered among my papers by persons unknown, apparently completed by individuals who had the audacity to imitate my style while possessing the good sense to improve upon it².

The manuscript concerns itself with strawberries, which are not actually berries at all but aggregate accessory fruits³. This botanical inaccuracy should prepare the reader for the many other inaccuracies that follow, including the suggestion that human economic systems might be designed to work properly⁴.

I have always maintained that the study of human behavior benefits from the same scientific detachment one brings to the observation of insects⁵. The present work applies this principle to the study of what economists call "resource allocation" and what normal people call "trying to get enough stuff to live on⁶." The results, I believe, are illuminating, though possibly not in the way the original authors intended⁷.

The story begins with a man named Bunto Fairweather, which is obviously a made-up name⁸. No parent would inflict such nomenclature on a child, unless they possessed the peculiar sense of humor that leads people to name their offspring after weather conditions⁹. Nevertheless, Bunto serves our purposes adequately, being neither too intelligent to believe what he's told nor too stupid to notice when what he's told contradicts what he observes¹⁰.

The tale that follows concerns the discovery of strawberry plants that work too well—a concept that will strike modern readers as either fantastical or redundant, depending on their experience with contemporary strawberries¹¹. These plants produce abundant fruit without requiring the constant inputs that make modern agriculture profitable for everyone except farmers and consumers¹².

What begins as a simple story about productive plants evolves into a complex examination of why human systems seem designed to work as poorly as possible while generating maximum profit for the people who design them to work poorly¹³. This paradox has puzzled philosophers for centuries, though it has never puzzled the people who profit from it¹⁴.

The reader will encounter footnotes throughout this work¹⁵. These serve multiple purposes: they provide additional information that would interrupt the narrative flow if included in the main text¹⁶; they allow the author to make observations that are too cynical for the main story¹⁷; and they give readers something to do with their eyes when the main narrative becomes too depressing to continue¹⁸.

I should note that any resemblance between the characters in this story and actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and probably actionable¹⁹. The corporations described herein are fictional, though their methods may seem familiar to anyone who has attempted to purchase durable goods, reliable services, or accurate information in recent decades²⁰.

The story is presented in the manner of the old serial novels, appearing in monthly installments over several months²¹. This allows readers to digest the implications gradually, rather than experiencing the full impact of artificial scarcity revelation all at once²². It also provides time for readers to observe their own economic systems and determine whether the satirical elements in this story are actually satirical²³.

Those who find the monthly wait unbearable may purchase the complete work as an electronic book for the modest sum of $4.99²⁴. This price point was selected to demonstrate that useful products can be made available at reasonable cost when not subjected to artificial scarcity mechanisms²⁵. Whether this demonstrates the author's commitment to abundance economics or merely his inability to charge more remains a matter for individual interpretation²⁶.

The story concludes with what literary critics call "an open ending," which means the author couldn't decide how things should turn out and decided to let readers figure it out for themselves²⁷. This approach has the advantage of making the story relevant to whatever actually happens in the real world, while avoiding the disadvantage of being wrong about the future²⁸.

I trust the reader will approach this work with the same spirit of scientific inquiry that one brings to the study of any curious natural phenomenon²⁹. The behavior of humans in economic systems is no less fascinating than the behavior of ants in colonies, though considerably more expensive to observe³⁰.

Will Cuppy

Posthumously, with assistance

Introduction Footnotes

¹ The phenomenon of dead authors writing about future events is less unusual than it appears, since most economic predictions are made by people whose understanding of economics died long before their bodies followed suit.

² Imitating a dead humorist's style while improving upon it requires considerable skill, questionable judgment, and access to the deceased author's unpublished notes, which may or may not have been obtained through entirely legal means.

³ Strawberries being aggregate accessory fruits rather than true berries demonstrates that botanical accuracy and common usage have about as much in common as economic theory and economic reality.

⁴ The suggestion that human systems might work properly is indeed inaccurate, though no more so than most other suggestions about human behavior found in academic literature.

⁵ Scientific detachment in the study of human behavior is easier to maintain when humans are observed from a safe distance, preferably through bulletproof glass.

⁶ The difference between "resource allocation" and "trying to get enough stuff to live on" illustrates the gap between how economists describe reality and how normal people experience it.

⁷ Results being illuminating in unintended ways is a common feature of scientific research, economic policy, and attempts to fix household appliances.

⁸ Obviously made-up names in fiction serve the same function as obviously made-up statistics in economics: they allow the author to make points without being sued for accuracy.

⁹ Parents who name children after weather conditions demonstrate the same optimism that leads economists to assume people behave rationally.

¹⁰ Characters who are neither too intelligent nor too stupid make ideal protagonists because they represent the vast majority of humanity, who muddle through life with just enough sense to get into trouble and just enough ignorance to be surprised by the consequences.

¹¹ The concept of things working too well will strike modern readers as fantastical because they have been conditioned to expect malfunction, or redundant because they assume malfunction is the intended function.

¹² Modern agriculture being profitable for everyone except farmers and consumers demonstrates the efficiency of systems designed to extract maximum value from the people who produce and consume the products.

¹³ Systems designed to work poorly while generating maximum profit for their designers represent the triumph of engineering over ethics, efficiency over effectiveness, and cleverness over wisdom.

¹⁴ Paradoxes that puzzle philosophers but never puzzle profiteers suggest that philosophy and profit operate according to different logical systems, with profit logic generally proving more practical.

¹⁵ Footnotes throughout this work serve as a parallel commentary system, allowing the author to maintain plausible deniability about his more cynical observations.

¹⁶ Additional information that would interrupt narrative flow if included in the main text is relegated to footnotes, where it can interrupt the reader's concentration instead.

¹⁷ Observations too cynical for the main story find refuge in footnotes, where cynicism is expected and therefore less shocking.

¹⁸ Footnotes giving readers something to do when the main narrative becomes depressing serve the same function as commercial breaks during tragic news broadcasts.

¹⁹ Resemblances being coincidental and probably actionable reflects the modern reality that truth and libel are often indistinguishable, making fiction safer than journalism.

²⁰ Fictional corporations whose methods seem familiar demonstrate that reality has become indistinguishable from satire, making satirists' jobs both easier and more depressing.

²¹ Monthly installments in the manner of old serial novels allow modern readers to experience the anxiety of waiting for resolution that previous generations took for granted.

²² Gradual digestion of artificial scarcity revelation prevents the psychological shock that might result from sudden exposure to the full scope of systematic abundance suppression.

²³ Time for readers to observe their own systems and determine whether satirical elements are actually satirical transforms readers from passive consumers into active researchers.

²⁴ The modest sum of $4.99 for the complete electronic work demonstrates pricing that prioritizes accessibility over maximum profit extraction.

²⁵ Reasonable pricing when not subjected to artificial scarcity mechanisms proves that affordability is a choice rather than an impossibility.

²⁶ Whether reasonable pricing demonstrates commitment to abundance economics or inability to charge more remains ambiguous, allowing readers to project their own interpretations onto the author's motives.

²⁷ Open endings that let readers figure things out for themselves transfer responsibility for resolution from author to audience, demonstrating either democratic principles or authorial laziness.

²⁸ Avoiding the disadvantage of being wrong about the future by not making specific predictions represents the ultimate in hedge-betting literary strategy.

²⁹ Scientific inquiry applied to human economic behavior requires the same detachment used to study other natural phenomena, though humans are generally less predictable than laboratory animals and more dangerous when cornered.

³⁰ Human economic behavior being more expensive to observe than ant colony behavior reflects the higher overhead costs of human systems, which require more resources to produce less efficiency than most insect societies.

PUBLICATION NOTICE

THE STRAWBERRY CONSPIRACY will be serialized monthly beginning next month, with each chapter available free to subscribers of The Modern Satirist quarterly review. The complete novella is available immediately as an electronic download for $4.99 at [publisher's website].

This represents an experiment in abundance economics: providing quality content at accessible prices while demonstrating that artificial scarcity in publishing is a choice rather than a necessity. Whether this experiment succeeds or fails will depend largely on whether readers choose to support abundance-based publishing models or continue to accept scarcity-based pricing structures.

The author (posthumously) and his collaborators welcome feedback, though they reserve the right to incorporate criticism into future footnotes, where it can be properly contextualized and gently mocked.

Next Month: Chapter One - "The Unusually Productive Plant" - In which Bunto Fairweather discovers that some strawberries have failed to read the manual on planned obsolescence.

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION

The Modern Satirist quarterly review is available by subscription for $19.99 annually, demonstrating that even satirical publications must participate in the economic systems they critique. Subscribers receive advance access to serialized content, exclusive footnotes, and the satisfaction of supporting writers who have chosen to mock the systems that pay them.

Electronic subscriptions are available for $12.99 annually, proving that digital distribution can reduce costs when not artificially inflated to protect obsolete business models.

Free samples are available to anyone who asks, because abundance-based publishing assumes that people who enjoy content will choose to support its creators, rather than assuming that people will only pay when forced to do so by artificial scarcity mechanisms.

This approach may prove either revolutionary or financially ruinous, but it will certainly provide material for future satirical works about the economics of satirical publishing.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

This tale was discovered among the papers of Will Cuppy (1884-1949), the American humorist and nature writer known for “How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes” and other works of satirical natural history. While Cuppy died long before the events described herein, his papers contained detailed notes for a work he apparently intended to call “The Plants Man,” along with extensive footnotes in his characteristic style.

The manuscript appears to have been completed by persons unknown, possibly members of what the text refers to as “the abundance network.” Whether this represents genuine prophecy, elaborate fiction, or documentary evidence of events yet to unfold remains a matter for readers to determine.

The strawberry plants mentioned in this account have not been officially verified by agricultural authorities, though reports of unusually productive strawberry varieties continue to circulate through informal networks. Readers are advised to draw their own conclusions about the relationship between fiction and reality.

As Cuppy himself might have noted: “The difference between a fairy tale and a true story is often a matter of timing.”

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THE PLANTSMAN: PRECOGNITIVE POSTCARDS

Chapter One: The Integral Compartment

Chapter Two: The Semiotic Signal Box

Chapter Three: The Hermeneutic Engine

TRANSITION: THE APPROACHING STATIONS

As I write this, the train is approaching two stations that don’t appear on any official schedule⁷⁵. The first is called “Conquest of Dough”⁷⁶—a place where the ancient human struggle for daily bread has been transformed into a complex financial instrument⁷⁷. The second is “The Clockwork Forest”⁷⁸—a destination where natural systems have been replaced by mechanical ones that simulate nature while extracting value from the simulation⁷⁹.

These stations represent the culmination of the journey I began documenting⁸⁰. They are places where the patterns I’ve been observing reach their logical conclusion⁸¹. Where the interpretive energy that powers our confusion finally encounters the reality it has been working so hard to avoid understanding⁸².

The postcards that follow will be written from these stations⁸³. They will describe what it looks like when human systems become so sophisticated at extracting value that they begin to extract the conditions necessary for their own existence⁸⁴. When the hermeneutic engine becomes so efficient at converting understanding into power that it eliminates the human capacity for understanding⁸⁵.

But they will also describe what happens when people stop trying to understand the system and start trying to understand each other⁸⁶. When interpretive energy is redirected from analysis to action⁸⁷. When the postcards stop being descriptions of where we’ve been and become invitations to where we might go⁸⁸.

The train is slowing down⁸⁹. The next station is approaching⁹⁰. Time to gather my postcards and prepare for whatever comes next⁹¹.

Chapter 1.

CHAPTER ONE: THE DISCOVERY

In Which Nature Makes a Mistake That Threatens Civilization

Bunto Fairweather¹ discovered the Everlasting Strawberry on a Tuesday, which was his first mistake. Tuesdays are traditionally reserved for mundane disasters—broken washing machines, tax demands, and the realization that one has run out of milk—not for discoveries that could revolutionize agriculture and thereby threaten the entire economic order².

The strawberry plant sat innocuously in Section 7-B of Perpetual Growth Nurseries³, between the genetically modified roses that bloomed for exactly thirty days before requiring replacement and the ornamental cabbages designed to wilt photogenically for Instagram posts. Unlike its neighbors, this particular plant showed no signs of the planned obsolescence that had made Perpetual Growth the third-largest horticultural corporation in the Northern Hemisphere⁴.

“Rog,” called Bunto to his colleague, who was busy explaining to a customer why their £200 Japanese maple had died after precisely thirteen months, “this strawberry hasn’t been watered in three weeks, and it’s producing more fruit than a government inquiry produces excuses.”

Rog Petrichor⁵ looked up from his customer consultation, where he was demonstrating the company’s new “Sympathy Guarantee”—a policy that offered emotional support but no financial compensation for plant mortality. “That’s impossible,” he replied, with the confidence of a man who had spent fifteen years watching expensive plants die on schedule. “Everything dies. It’s the first law of horticulture and the foundation of our business model⁶.”

But the strawberry plant, apparently unaware of economic necessity, continued producing perfect red fruit while its soil remained as dry as a banker’s conscience⁷. Bunto picked one of the berries and bit into it, expecting the usual disappointment that characterized modern fruit—beautiful appearance concealing flavorless flesh bred for shelf life rather than taste⁸.

Instead, he experienced what he later described to the Corporate Investigation Committee as “the taste of strawberries as they existed before we improved them⁹.” The fruit was sweet without being cloying, tart without being bitter, and possessed a flavor so intense that it seemed to contain the essence of every strawberry that had ever existed, plus several that hadn’t been invented yet¹⁰.

“Rog,” said Bunto, his voice carrying the tone of a man who has just realized he is holding either a miracle or a catastrophe, “we need to test this.”

They spent the next week conducting experiments that would have impressed Darwin and horrified the Perpetual Growth board of directors¹¹. The plant required no water, no fertilizer, and no pesticides. It produced fruit continuously, with each berry maintaining perfect ripeness for weeks without refrigeration. Most disturbing of all, the plant showed signs of actually improving the soil around it, enriching rather than depleting the earth—a behavior so contrary to modern agricultural principles that it bordered on the subversive¹².

“This,” announced Rog after seven days of observation, “is either the greatest discovery in agricultural history or the most dangerous threat to agricultural economics since someone invented the plow¹³.”

Bunto nodded grimly. He had worked in the nursery business long enough to understand that the two statements were not contradictory¹⁴.

Chapter One Footnotes

¹ Bunto Fairweather was named by parents who believed that optimistic nomenclature could overcome genetic pessimism. They were wrong, but their failure produced a man ideally suited for discovering inconvenient truths.

² The economic order depends on scarcity, real or artificial. Abundance is the enemy of profit margins, which explains why economists treat it as a theoretical impossibility rather than a practical goal.

³ Perpetual Growth Nurseries was founded on the principle that plants, like economies, should grow continuously until they collapse. The company’s motto, “Growth Through Planned Decline,” captured the essential paradox of modern capitalism.

⁴ The Northern Hemisphere’s horticultural industry was dominated by three corporations that had successfully cartelized plant mortality, ensuring that gardens required constant replacement rather than occasional maintenance.

⁵ Rog Petrichor’s surname means “the pleasant smell of earth after rain,” which was ironic since he spent most of his time explaining why earth smelled of death and disappointment.

⁶ The first law of horticulture, as taught in business schools, states that profitable plants must die on predictable schedules. Plants that live indefinitely threaten quarterly earnings projections.

⁷ Bankers’ consciences are notably arid, having been desiccated by years of compound interest calculations and mortgage foreclosure procedures.

⁸ Modern fruit breeding prioritizes appearance, shelf life, and shipping durability over flavor, nutrition, or consumer satisfaction. This represents the triumph of logistics over biology.

⁹ The Corporate Investigation Committee was established to investigate discoveries that threatened established business models. Its members were selected for their ability to find problems with solutions.

¹⁰ The concept of fruit containing flavors that hadn’t been invented yet troubled the committee’s scientific advisors, who preferred their impossibilities to be mathematically rather than gastronomically expressed.

¹¹ Darwin would have been impressed by the plant’s adaptive success; the board of directors would have been horrified by its refusal to participate in planned obsolescence schemes.

¹² Soil improvement by plants violates the fundamental principle of extractive agriculture, which holds that farming should deplete resources rather than regenerate them. Regenerative plants threaten the fertilizer industry’s business model.

¹³ The plow was history’s first great labor-saving device that actually created more work, establishing a pattern that modern technology continues to follow with admirable consistency.

¹⁴ The greatest discoveries in human history have typically been the most dangerous threats to existing power structures, which explains why they are usually suppressed, ignored, or monetized beyond recognition.

THE PLANTSMAN: PRECOGNITIVE POSTCARDS & THE PLANTS MAN A Natural History of Artificial Scarcity

Prologue Footnotes

CHAPTER ONE: THE DISCOVERY

CHAPTER TWO: THE CORPORATE RESPONSE

CHAPTER THREE: THE WEATHER CONSPIRACY

CHAPTER FOUR: THE WALKING INVESTIGATION

CHAPTER FIVE: THE CIRCLE OF BLAME

CHAPTER SIX: THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD OF ABUNDANCE

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE ALGORITHM OF WANT

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE GREAT CONVERGENCE

CHAPTER NINE: THE CHOICE POINT

CHAPTER TEN: THE STRAWBERRY REVOLUTION

EPILOGUE: THE GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS

FINAL FOOTNOTE

NEXT MONTH: Chapter Four of The Strawberry Conspiracy - "The Walking Investigation" - In which pedestrian research reveals automotive truths, and abundance networks operate in plain sight.

COMING SOON: The Conquest of Dough - A postcards-from-the-future examination of how daily bread became a derivative instrument.

ALSO FORTHCOMING: The Clockwork Forest - Reports from a place where natural systems have been replaced by mechanical ones that simulate nature while extracting value from the simulation.

All available as part of The Modern Satirist quarterly review subscription, or as individual electronic downloads for readers who prefer their dystopian humor in concentrated doses.

Link to Other Orger Lewis Books , This one will appear later today.