The Clockwork Forest: A Novel in Ten Chapters. The Antedote To Israel/US v Iran Binary, Every Body is the BIS's Bitch

In the Manner of G.K. Chesterton. Corrupting the Morals of Monica.( The panopticon Jailer bot.)

The Clockwork Forest: A Novel in Ten Chapters

In the Manner of G.K. Chesterton

Chapter 1: The Paradox of the Perfectly Planned Crisis

There is something magnificently absurd about a world where the most unbelievable conspiracies turn out to be documented fact, while the most obvious truths are dismissed as fantasy. Robin sat in the corner café of what had once been called Fleet Street, now rechristened "Digital Democracy Boulevard" by the Ministry of Truthful Nomenclature, reading a newspaper that insisted the latest economic crisis was entirely unpredictable.

"Unpredictable," Robin muttered to Christine, who was stirring her tea with the mechanical precision of someone who had given up expecting it to taste like anything but surveillance. "Rather like calling a train wreck unpredictable when you've got the timetable, the track layout, and a front-row seat to watch the engineer drinking himself senseless."

Christine looked up from her tablet, where she had been scrolling through the morning's algorithmic news feed. "The beauty of modern crisis management," she observed, "is that they no longer need to hide the conspiracy. They simply label anyone who notices it as a conspiracy theorist. It's rather like painting 'INVISIBLE' on an elephant and then expressing surprise when people claim to see a large grey mammal in the room."

Charlie emerged from behind his copy of The Financial Times, which he read daily as a form of masochistic entertainment. "Speaking of elephants," he said, "I see the Bank for International Settlements has issued another warning about 'systemic risks' while simultaneously implementing the very policies that create those risks. It's like a doctor prescribing poison while warning about the dangers of toxicity."

The café around them hummed with the conversations of the digitally employed—those whose jobs consisted primarily of managing the management of other people's management. Chesterton would have recognized the type: people so busy organizing efficiency that they had forgotten what they were supposed to be efficient at 1.

"The real paradox," Robin continued, warming to his theme, "is that we live in an age of unprecedented transparency where nothing can be seen clearly. Every transaction is recorded, every movement tracked, every thought catalogued—and yet the actual workings of power remain as mysterious as ever."

Christine nodded, her expression growing serious. "It's the digital panopticon perfected. Bentham's prison design, but instead of guards watching prisoners, we have algorithms watching everyone, including the guards. The watchers are watched by watchers who are themselves watched, in an infinite regression of surveillance that somehow manages to obscure rather than illuminate."

Charlie folded his newspaper with the decisive snap of a man who had reached his daily quota of institutional absurdity. "And the most delicious irony of all is that they call it freedom. Digital freedom, democratic freedom, market freedom—every kind of freedom except the one that matters: the freedom to be left alone."

Chapter 2: The Democracy of Algorithms

The trio had moved to their usual table by the window, where they could observe the morning parade of what Charlie called "the digitally domesticated"—citizens who had so thoroughly internalized their surveillance that they carried it with them like a beloved pet.

"Democracy," Robin began, gesturing toward the street where people walked with their faces buried in screens, "has been replaced by something far more insidious than tyranny. It's been replaced by convenience."

Christine looked up from her tablet, where she had been reading about the latest "democratic innovation"—an AI system that could predict voting patterns with 97% accuracy. "The genius of the modern system is that it gives people exactly what they want while ensuring they never want anything dangerous. It's democracy by algorithm, representation by recommendation engine."

"Rather like asking people what they want for dinner," Charlie observed, "but only after you've programmed their taste buds to crave whatever you happen to be serving."

The conversation was interrupted by a notification on Christine's device—a cheerful ping that informed her she had been selected for a "Democratic Participation Opportunity." The screen displayed a series of multiple-choice questions about local governance, each answer pre-weighted by an algorithm that had analyzed her shopping habits, social connections, and biometric responses to previous surveys.

"Behold," she said, holding up the screen, "democracy in action. I can choose between Option A, which the algorithm knows I'll prefer based on my psychological profile, Option B, which is designed to make Option A look reasonable, and Option C, which is so obviously absurd that only a madman would select it."

Robin leaned over to examine the screen. "And yet they'll count this as genuine democratic participation. Your voice has been heard, your opinion registered, your civic duty fulfilled. The fact that your opinion was manufactured by the same system that's asking for it is merely a technical detail."

Charlie chuckled, but there was no humor in it. "It's the perfect crime, really. They've stolen democracy while convincing everyone they're preserving it. It's like a pickpocket who hands you back your empty wallet while thanking you for the donation."

The irony, as Chesterton understood, was that the very technologies designed to enhance democratic participation had instead perfected the art of manufacturing consent 2. The algorithms didn't suppress dissent—they simply ensured that dissent took forms that were either ineffective or easily co-opted.

"The real question," Christine said, closing her tablet with a decisive click, "is whether we're witnessing the death of democracy or its evolution into something entirely different. Something that maintains the forms and rituals of democratic participation while hollowing out its substance."

"Perhaps," Robin suggested, "the answer is both. Democracy dies, but its ghost continues to haunt the machine, providing legitimacy for a system that has transcended the need for genuine popular consent."

Chapter 3: The Usury of Attention

Their conversation had attracted the attention of a young man at the neighboring table, who had been pretending to work on his laptop while obviously eavesdropping. He was the sort of person who wore his surveillance as a fashion statement—smart watch, fitness tracker, wireless earbuds, and a phone that never left his hand.

"Excuse me," he said, with the earnest enthusiasm of someone who had just discovered fire, "but I couldn't help overhearing your conversation. Are you saying that technology is bad? Because I have to disagree. My apps have made my life so much more efficient."

Robin smiled with the patience of a man who had been expecting this interruption. "Not bad, my dear fellow. Brilliant. Absolutely brilliant. The question isn't whether technology is good or bad—it's who controls it and to what end."

The young man looked puzzled. "But I control my technology. I choose which apps to use, which services to subscribe to, which content to consume."

"Ah," said Christine, "but do you? Or do you simply choose from a menu that's been carefully curated to ensure that all choices lead to the same destination?"

Charlie leaned forward, his expression growing serious. "Tell me, what did you pay for your phone?"

"Eight hundred dollars," the young man replied proudly. "But it was worth it for all the features."

"And what do you pay monthly for your data plan, your streaming services, your app subscriptions?"

The young man began calculating, his confidence visibly deflating as the numbers added up. "Maybe... two hundred dollars a month? But that's for everything—entertainment, productivity, social connection..."

"So in a year," Robin calculated, "you spend roughly three thousand dollars to carry a device that tracks your every movement, records your every conversation, and analyzes your every preference. You're paying handsomely for the privilege of being surveilled."

The young man's face showed the dawning realization that he might not be the customer in this transaction. "But... but I get value from it. I can connect with friends, access information, be entertained..."

"Indeed," Christine agreed. "And in medieval times, serfs received value from their feudal lords—protection, shelter, a place in the social order. The question isn't whether you receive value, but whether the value you receive is proportional to the value you provide."

This was the modern form of usury that Chesterton would have recognized immediately—not the simple lending of money at interest, but the systematic extraction of human attention, data, and autonomy in exchange for convenience and connection 3. The interest was paid not in currency but in the coin of human consciousness itself.

"The old usurers," Charlie explained, "lent money and demanded repayment with interest. The new usurers lend convenience and demand repayment with your soul—or at least, with your attention, your privacy, and your autonomy."

The young man sat back, his phone suddenly feeling heavier in his hand. "So what's the alternative? Go back to the stone age?"

"Not at all," Robin replied. "The alternative is to remember that technology should serve human purposes, not the other way around. To insist that our tools enhance our humanity rather than diminish it."

Chapter 4: The Theology of Progress

The conversation had drawn a small crowd, as conversations in public spaces sometimes do when they touch on subjects that people think about but rarely discuss. An elderly woman with a walking stick had paused nearby, listening with the sharp attention of someone who had lived through enough historical changes to recognize a pattern.

"You young people," she said, settling into an empty chair with the authority of age, "talk as if this is all new. But I remember when television was going to educate the masses, when computers were going to democratize information, when the internet was going to free us all from the gatekeepers."

Christine nodded respectfully. "And what happened instead?"

"What always happens," the woman replied. "The same people who controlled the old systems figured out how to control the new ones. The faces changed, the technology advanced, but the fundamental relationships of power remained the same."

This was the insight that Chesterton had grasped about progress—that it was not a neutral force but a direction, and that direction was determined by those who had the power to point the way 4. The theology of progress assumed that technological advancement necessarily meant human advancement, but history suggested otherwise.

"The real religion of our time," Robin observed, "isn't Christianity or Islam or Buddhism. It's Progressivism—the faith that whatever comes next must be better than what came before, simply because it comes next."

The elderly woman chuckled. "In my day, we called that superstition."

Charlie leaned forward, intrigued. "But surely some progress is real? Medical advances, communication technologies, scientific understanding?"

"Of course," the woman agreed. "But progress in one area often means regress in another. We can communicate instantly with people on the other side of the world, but we've lost the ability to have a conversation with our neighbors. We can access all human knowledge with a few keystrokes, but we've forgotten how to think for ourselves."

The young man with the phone looked uncomfortable. "But that's just the price of advancement. Every generation has to adapt to new technologies."

"Adapt," Christine repeated thoughtfully. "That's an interesting word choice. It implies that we must change to fit the technology, rather than shaping the technology to fit our needs."

This was the theological error at the heart of technological progressivism—the assumption that human beings must conform to the demands of their tools, rather than demanding that tools serve human purposes. It was a form of idolatry that would have appalled Chesterton, who understood that the proper relationship between humans and their creations was one of mastery, not servitude.

"The question," the elderly woman said, rising to leave, "is not whether we can adapt to our technologies, but whether we should. Some adaptations are improvements. Others are degradations. The trick is knowing the difference."

Chapter 5: The Manufacture of Consent

As the elderly woman departed, her walking stick tapping a steady rhythm on the café floor, the remaining group fell into a contemplative silence. The young man with the phone seemed to be wrestling with ideas that challenged his fundamental assumptions about the world he inhabited.

"I keep thinking about what she said," he began slowly, "about the same people controlling the new systems. But how is that possible? The internet was supposed to democratize everything. Anyone can start a blog, create content, build an audience."

Robin smiled with the gentle patience of a teacher who had been waiting for exactly this question. "Indeed they can. And that's precisely the genius of the system. It creates the illusion of democratization while perfecting the mechanisms of control."

Christine pulled out her tablet and navigated to a social media platform. "Watch this," she said, showing the screen to the group. "I'm going to search for information about, let's say, economic inequality."

The search results populated instantly: a mixture of news articles, opinion pieces, videos, and social media posts. At first glance, it appeared to be a diverse array of perspectives from multiple sources.

"Now," Christine continued, "let me show you something interesting." She accessed the platform's analytics dashboard, revealing the algorithmic machinery beneath the surface. "Every piece of content you see has been weighted, ranked, and filtered based on factors you can't see: your browsing history, your social connections, your demographic profile, your previous engagement patterns."

The young man leaned closer, his expression growing troubled. "So the information I'm seeing..."

"Is precisely the information the algorithm has determined you're most likely to engage with," Charlie finished. "Not necessarily the most accurate, not the most important, not the most challenging to your existing beliefs—just the most likely to keep you scrolling."

This was the modern manufacture of consent that would have fascinated and horrified Chesterton in equal measure. Unlike the crude propaganda of earlier eras, which sought to impose a single narrative, the new system created the illusion of choice while ensuring that all choices led to the same destination 1.

"But surely," the young man protested, "people can still seek out alternative viewpoints if they want to?"

"Can they?" Robin asked. "When the algorithm learns that you occasionally seek out dissenting opinions and begins feeding you controlled opposition—viewpoints that appear to challenge the mainstream but actually reinforce it by making genuine alternatives seem extreme or ridiculous?"

Christine nodded. "It's like being offered a choice between vanilla and French vanilla ice cream and being told you're experiencing the full spectrum of frozen dessert options."

The young man sat back, his phone now lying forgotten on the table. "So what you're saying is that the entire information ecosystem is... manufactured?"

"Not manufactured," Charlie corrected. "Curated. Shaped. Guided. The content is real, the opinions are genuine, the debates are authentic—they're just taking place within parameters that have been carefully established to ensure that no genuinely threatening ideas gain traction."

This was the true sophistication of modern power—it didn't need to suppress dissent because it had learned to channel dissent into forms that ultimately served its purposes. It was a system that Chesterton, with his understanding of paradox, would have recognized as the perfect inversion of freedom: a tyranny that operated through the mechanisms of liberty itself.

Chapter 6: The Economics of Attention

The café had grown busier as the morning progressed, filling with the usual assortment of remote workers, students, and what Charlie privately called "the laptop class"—people whose jobs seemed to consist primarily of attending virtual meetings about other virtual meetings.

"The fundamental economic transformation of our time," Robin began, watching a nearby table where four people sat together, each staring at their own screen, "isn't the shift from manufacturing to services, or from analog to digital. It's the shift from an economy based on the production of goods to an economy based on the extraction of attention."

The young man, who had introduced himself as Marcus, looked up from his phone, which he had been unconsciously checking despite their conversation about digital manipulation. "Extraction? That sounds rather sinister."

"Is it?" Christine asked. "Consider the business model of the platforms you use daily. They provide services—search, social networking, entertainment—apparently for free. But nothing is actually free. So what are you paying with?"

Marcus thought for a moment. "My data, I suppose. My personal information."

"Deeper than that," Charlie said. "Your attention itself. Your consciousness. Your mental bandwidth. These platforms are designed to capture and hold your attention for as long as possible, because attention is what they sell to advertisers."

This was the new form of capitalism that Chesterton could never have imagined—one in which the primary commodity being extracted wasn't labor or natural resources, but human consciousness itself. The factories had been replaced by algorithms, the assembly lines by news feeds, but the fundamental relationship remained the same: a small number of people profiting from the systematic exploitation of a much larger number.

"But I choose what to pay attention to," Marcus protested, even as his eyes drifted toward his phone screen, which had just lit up with a notification.

"Do you?" Robin asked gently. "Or have you been trained to pay attention to what generates the most profit for the platforms?"

Christine leaned forward. "Here's an experiment. For the next hour, try to focus entirely on our conversation without checking your phone, without glancing at any screens, without allowing your attention to be pulled away by external stimuli."

Marcus accepted the challenge with the confidence of someone who believed he was in control of his own mind. Within ten minutes, he was visibly struggling, his hand reaching unconsciously for his phone, his eyes darting toward the screens of other café patrons.

"This is harder than I expected," he admitted.

"Of course it is," Charlie said. "You've been trained, through years of conditioning, to expect constant stimulation, immediate gratification, and perpetual connectivity. Your attention span has been systematically fragmented to match the needs of the attention economy."

The irony was profound: in an age of unprecedented access to information, people were becoming less capable of sustained thought. In an era of constant connectivity, they were becoming increasingly isolated. In a time of infinite entertainment options, they were growing more bored and restless than ever before.

"The old capitalists," Robin observed, "exploited workers' bodies and labor. The new capitalists exploit their minds and attention. In many ways, it's a more total form of exploitation because it follows you home, invades your private thoughts, and shapes your very sense of self."

Chapter 7: The Illusion of Choice

As Marcus struggled with his self-imposed digital detox, a new character entered their ongoing drama. She was a woman in her thirties, impeccably dressed in the uniform of the professional class—expensive but understated clothing that signaled both success and conformity. She had been listening to their conversation from a nearby table and finally approached with the confident stride of someone accustomed to being heard.

"I'm sorry to interrupt," she said, though her tone suggested she wasn't particularly sorry, "but I couldn't help overhearing your discussion. I'm Sarah, and I work in digital marketing. I think you're being rather unfair to the technology industry."

Robin gestured to an empty chair. "Please, join us. We're always eager to hear from someone with inside knowledge."

Sarah settled into the chair with practiced ease. "The thing is, we're not manipulating people. We're giving them what they want. Our algorithms are simply very good at predicting preferences and delivering relevant content."

"Ah," said Christine, "the 'revealed preference' argument. People choose to engage with our content, therefore they must want it."

"Exactly," Sarah replied. "If people didn't want to see our ads, watch our videos, use our platforms, they wouldn't. The market is democratic—people vote with their clicks."

Charlie leaned back, a slight smile playing on his lips. "Tell me, Sarah, do you have children?"

"I do. Two daughters, ages eight and ten."

"And do you allow them unlimited access to candy?"

Sarah looked puzzled. "Of course not. That would be terrible for their health."

"But surely," Charlie continued, "if you offered them a choice between vegetables and candy, they would democratically choose the candy. By your logic, you should respect their revealed preferences."

"That's different," Sarah protested. "Children don't have fully developed judgment. They can't understand the long-term consequences of their choices."

"Indeed," Robin said quietly. "And what makes you think adults are any different when it comes to digital consumption? What makes you think that people's immediate impulses represent their deeper preferences or long-term interests?"

This was the fundamental flaw in the ideology of digital capitalism—the assumption that momentary engagement represented genuine choice, that addictive design patterns reflected authentic preferences, that the ability to click represented meaningful agency 2.

Sarah shifted uncomfortably. "But we're not forcing anyone to use our platforms. People are free to leave at any time."

"Are they?" Marcus asked, surprising everyone, including himself. "I've been trying not to check my phone for thirty minutes, and it's genuinely difficult. And that's just for thirty minutes. What about people whose jobs require constant connectivity? Whose social relationships exist primarily online? Whose access to information, entertainment, and services depends on these platforms?"

Christine nodded. "It's like saying people are free to stop using electricity. Technically true, but practically meaningless in a society built around electrical infrastructure."

Sarah's confidence was beginning to waver. "But surely you're not suggesting we go back to a pre-digital world? These technologies have brought enormous benefits—global communication, access to information, economic opportunities..."

"No one is suggesting we abandon technology," Robin assured her. "We're suggesting we think more carefully about how it's designed and deployed. About who controls it and for what purposes. About whether the current system serves human flourishing or merely human engagement."

The distinction was crucial: engagement was not the same as flourishing, just as consumption was not the same as satisfaction, and connectivity was not the same as community. The digital economy had optimized for metrics that were easy to measure—clicks, views, time spent—rather than outcomes that actually mattered to human wellbeing.

Chapter 8: The Surveillance Capitalism Paradox

Sarah's professional composure was beginning to crack as the conversation challenged the fundamental assumptions of her industry. She pulled out her own phone—a gesture that didn't go unnoticed by the others—and began scrolling through what appeared to be work emails.

"I need to check something," she said, though it was clear she was seeking refuge in the familiar comfort of her digital environment.

"Of course," Robin said gently. "But while you're checking, notice what you're checking. Notice the little dopamine hit when you see a new notification, the slight anxiety when you don't. Notice how the platform is designed to keep you engaged just a little longer than you intended."

Sarah paused, her finger hovering over the screen. For the first time, she seemed to be observing her own behavior rather than simply performing it.

"This is what we call surveillance capitalism," Christine explained. "It's not just that our data is being collected—it's that our behavior is being modified in real-time to generate more data, more engagement, more profit."

Marcus, who had been quietly observing his own digital withdrawal symptoms, looked up with sudden clarity. "It's like being in a casino, isn't it? The lights, the sounds, the intermittent rewards—everything designed to keep you playing just a little longer."

"Precisely," Charlie agreed. "Except the casino is in your pocket, available twenty-four hours a day, and you're not just gambling with money—you're gambling with your attention, your relationships, your mental health."

Sarah slowly put her phone face-down on the table. "But surely people can learn to use these tools responsibly? To set boundaries, to maintain self-control?"

"Some can," Robin acknowledged. "Just as some people can drink alcohol responsibly, some can gamble occasionally without becoming addicted, some can eat sugar in moderation. But when you design systems to be as addictive as possible and then blame individuals for lacking willpower, you're essentially arguing that the solution to industrial pollution is for everyone to hold their breath."

This was the core paradox of surveillance capitalism: it required individual solutions to systemic problems, personal responsibility in the face of institutional manipulation, private virtue in response to public vice 3. It was like asking people to swim upstream while increasing the current.

"The real question," Christine said, "isn't whether individuals can resist these systems, but whether we should have to. Whether a society that requires heroic levels of self-control just to maintain basic mental hygiene is really the society we want to live in."

Sarah was quiet for a long moment, staring at her phone as if seeing it for the first time. "I tell myself I'm helping businesses reach their customers more effectively. That I'm making advertising more relevant, more useful."

"And perhaps you are," Robin said kindly. "But you're also participating in a system that treats human attention as a resource to be mined, human psychology as a vulnerability to be exploited, human relationships as data points to be analyzed."

The tragedy, as Chesterton would have understood, was not that people like Sarah were evil, but that they were trapped in systems that made evil outcomes almost inevitable, regardless of individual intentions. The road to digital hell was paved with user experience improvements.

Chapter 9: The Resistance of the Real

As the afternoon wore on, their impromptu symposium had attracted a diverse collection of listeners and participants. The café had become an unlikely forum for questions that were rarely asked in polite society, let alone answered honestly.

An older gentleman in a worn tweed jacket had been listening from a corner table, occasionally nodding or shaking his head at various points in the conversation. Finally, he approached their table with the deliberate gait of someone who had something important to say.

"Forgive the intrusion," he said in an accent that suggested either Oxford or a very good imitation thereof, "but I couldn't help but be reminded of something Chesterton wrote about the modern world. He said that the trouble with the modern world was not that it was unreasonable, but that it was nearly reasonable. Nearly, but not quite."

Robin's eyes lit up with recognition. "Professor Williams, isn't it? I attended your lecture on medieval economics last year."

The professor smiled. "Guilty as charged. And I must say, your conversation today has been far more illuminating than most academic conferences I've attended."

He settled into a chair that someone had procured from a neighboring table. "The parallel to Chesterton's observation is striking. The digital world appears to be nearly free, nearly democratic, nearly empowering. Nearly, but not quite."

Sarah, who had been unusually quiet since putting away her phone, looked up with interest. "What do you mean by 'nearly'?"

"Well," the professor began, settling into his element, "consider the promise of the internet: universal access to information, global connectivity, democratized publishing, economic opportunity for all. Each of these promises has been partially fulfilled, but in ways that ultimately serve to concentrate rather than distribute power."

Marcus nodded slowly. "Like how anyone can start a YouTube channel, but the algorithm determines who gets seen."

"Exactly. Or how everyone can access information, but the search results are curated by algorithms designed to maximize engagement rather than truth. Or how global connectivity is possible, but the platforms that enable it are controlled by a handful of corporations."

Christine leaned forward. "It's the perfect totalitarian system because it delivers just enough freedom to prevent revolution while maintaining total control over the parameters within which that freedom can be exercised."

This was the insight that would have fascinated Chesterton: that the most effective tyranny was not one that obviously oppressed, but one that created the illusion of liberation while perfecting the mechanisms of control 4. It was tyranny with a human face, oppression with user-friendly design.

"But surely," Sarah said, though with less conviction than before, "there must be ways to reform the system? To maintain the benefits while addressing the problems?"

Professor Williams stroked his beard thoughtfully. "That's the question, isn't it? Can a system built on the extraction and manipulation of human attention be reformed to serve human flourishing? Or are the problems inherent in the fundamental architecture?"

"It's like asking whether you can reform a casino to promote financial responsibility," Charlie observed. "The entire business model depends on people making irrational decisions. Remove that, and you no longer have a casino."

The professor nodded. "Precisely. The surveillance capitalism model depends on capturing and holding attention, on creating psychological dependency, on harvesting data from human behavior. These aren't bugs in the system—they're features. They're how the system generates value."

Robin stood up and walked to the window, looking out at the street where people moved like sleepwalkers, their faces illuminated by the glow of their screens. "So what's the alternative? How do we resist a system that has made resistance nearly impossible?"

"Perhaps," the professor suggested, "we start by remembering what we're resisting for. What human values, what ways of being, what forms of relationship we want to preserve or recover."

Chapter 10: The Clockwork Forest

As evening approached, the café began to empty, but their small group remained, bound together by a conversation that had taken on a life of its own. The professor had ordered another tea, Sarah had finally turned off her phone completely, and Marcus was experimenting with what he called "analog thinking"—actually writing notes with a pen on paper.

"I keep coming back to this image," Robin said, sketching something on a napkin. "A clockwork forest. All the trees perfectly synchronized, moving in mechanical harmony, beautiful and efficient and utterly lifeless."

Christine looked at the sketch. "That's what the digital world feels like sometimes. Everything connected, everything optimized, everything responding to the same algorithmic rhythms."

"But what would a real forest look like?" Marcus asked. "In this metaphor, I mean."

Professor Williams smiled. "Messy. Chaotic. Unpredictable. Trees growing at different rates, in different directions, according to their own nature and the accidents of their environment. Some thriving, some struggling, some dying to make room for new growth."

"Inefficient," Sarah added, though she was smiling as she said it.

"Gloriously inefficient," Robin agreed. "And alive. Actually alive, not just simulating life."

This was the heart of their resistance: not a rejection of technology per se, but a rejection of the clockwork vision of human existence. The insistence that life was more than optimization, that meaning emerged from mess, that the most important things—love, creativity, wisdom, joy—could not be algorithmatized.

The Revolution Will Not Be Algorithmized.

(After Gil Scott-Heron, 2024)

The Revolution Will Not Be Algorithmized

(After Gil Scott-Heron, 2024)

You will not be able to scroll mindlessly, brother

You will not be able to plug in, log on, and tune out

You will not be able to doomscroll on Adderall

Or skip reels for DoorDash during buffer spins

Because the revolution will not be algorithmized

The revolution will not be algorithmized

The revolution will not be brought to you by TikTok

In four vertical parts with sponsored interruptions

The revolution will not show you deepfakes of Trump

Pumping fists at a rally led by Steve Bannon, MTG, and Netanyahu

To meme stocks seized from a Reddit basement

The revolution will not be algorithmized

The revolution will not stream on Netflix Originals

And will not star Zuckerberg’s metaverse avatars or Musk’s cybertrucks

The revolution will not give your profile clout

The revolution will not filter your flaws

The revolution will not make you go viral overnight

Because the revolution will not be algorithmized, brother

There’ll be no clips of you and Ye

Pushing conspiracy threads on 4chan’s dark boards

Or trying to NFT your lunch on a blockchain

CNN can’t fact-check the truth at 8:32

Or trend on 29 alt accounts

The revolution will not be algorithmized

There’ll be no livestreams of cops kneeling on necks

On loop for the timeline

No AI-generated eulogies for Breonna

No slow-mo montages of AOC

Strolling through Mar-a-Lago in a Patagonia vest

She’s been saving for the Resistance™

Stranger Things, The Crown, and House of the Dragon

Will no longer be so damn distracting

And influencers won’t care if Kylie finally broke the internet

Because the people will be in the streets swiping left on despair

The revolution will not be algorithmized

There’ll be no highlights on Fox or MSNBC

No thirst traps of Silicon Valley’s "visionaries"

Or Peter Thiel prepping bunkers in New Zealand

The anthem won’t be written by ChatGPT

Or Sam Altman, nor sung by Drake, Taylor Swift, or AI Drake

The revolution will not be algorithmized

The revolution will not buffer endlessly

After ads for Meta’s VR hellscape or crypto rug pulls

You won’t need to worry about bots in your DMs

The Palantir spyware or the microchips in your mRNA

The revolution will not pair with Prime

The revolution won’t be a Substack essay

The revolution will drag you off mute

The revolution will not be algorithmized

Will not be algorithmized

Will not be algorithmized

The revolution’s no deepfake, brothers

The revolution will be offline.

"So how do we plant seeds of the real forest in the clockwork one?" Charlie asked.

"Perhaps," the professor suggested, "we start with conversations like this one. With moments of genuine human connection that can't be commodified or optimized. With questions that don't have easy answers and problems that can't be solved by apps."

Sarah looked around the table at these people who had been strangers a few hours ago and who had somehow become something like friends. "You know, I haven't checked my phone in over an hour, and I don't miss it. I feel more... present. More here."

"That's the beginning," Christine said. "Presence. Attention given freely rather than extracted forcibly. Consciousness as a gift rather than a resource."

Marcus was still writing with his pen, the scratching sound somehow comforting in the digital silence. "I'm thinking about my job. About whether what I do actually contributes to human flourishing or just to the machinery of extraction."

"That's a question worth sitting with," Robin said. "Not rushing to answer, not solving immediately, just... sitting with."

As they prepared to leave, each going their separate ways into the evening, there was a sense that something had shifted. Not dramatically, not obviously, but genuinely. They had created, for a few hours, a small clearing in the clockwork forest—a space for real conversation, authentic questioning, genuine human connection.

"Same time next week?" the professor asked, and they all nodded, understanding that they had stumbled onto something worth preserving.

Walking out into the street, Robin looked up at the sky, barely visible through the glow of digital billboards and LED streetlights. Somewhere above the electronic noise, stars were shining—ancient, inefficient, gloriously real. In the clockwork forest of the modern world, they had found a way to remember what it meant to be human.

The conquest of AI, it turned out, was not about defeating artificial intelligence, but about refusing to become artificial themselves. It was about maintaining the wild, unpredictable, beautifully inefficient reality of human consciousness in a world increasingly designed to simulate, extract, and control it.

And perhaps that was enough. Perhaps it was everything.

End of Novel

Sources: 1Father_Brown

2 the-man-who-was-thursday/

3 the-fallacy-of-success/literary-devices/

Metaphor's for Tyranny

Algorithms are not like poems.

A poem is like an

algorithm. Not

in itself but similar.

Algorithms are similies for

poetry.

Algorithms are not like

poems which are

streams of conciousness that

enliven and awaken.

A metaphor that inspires the

imagination of possibilities.

Not a modelled conformity of

determinitistic tyranny.

Algorithms are a metaphor

for tyranny.

Roger G Lewis 2025

# Going Direct Series Review - Part 1: The Clockwork Forest

## A Review of Roger Lewis's AI-Enhanced Literary Journey

The Clockwork Forest: The Conquest of AI,

The Conquest of Dough sequel.

A Ruskinian Retrospective on Roger G. Lewis's Tetralogy of Modern Discontent

The Conquest of Dough. Trump The Cherry Marine Shining J R Ewings Shoes.

EVENT 202: The Sequel

A Novel in Ten Chapters In the manner of G.K. Chesterton

The Shoe-Shiner's Paradox: A Meditation on Power, Oil, and the Great Game. The Bank of International Settlements V Big Oil

The Elephant in the Room.

Links are in the Substack to those posts for listeners interested is the essential unfolding of this Human Curated corruprion of the morals of (Monica) the anthropomorphism of the Panopticon Jailer Bot.

# Going Direct Series Review - Part 1: The Clockwork Forest

# Going Direct Series Review - Part 1: The Clockwork Forest

A Ruskinian Retrospective on Roger G. Lewis's Tetralogy of Modern Discontent

https://books2read.com/u/4XYJ25 You can Buy the Novel which re prints the 3 poems at this link.

A Ruskinian Retrospective on Roger G. Lewis's Tetralogy of Modern Discontent: From Iron Laws to Algorithmic Tyranny

Introduction: The Clockwork Forest and the Conquest of AI

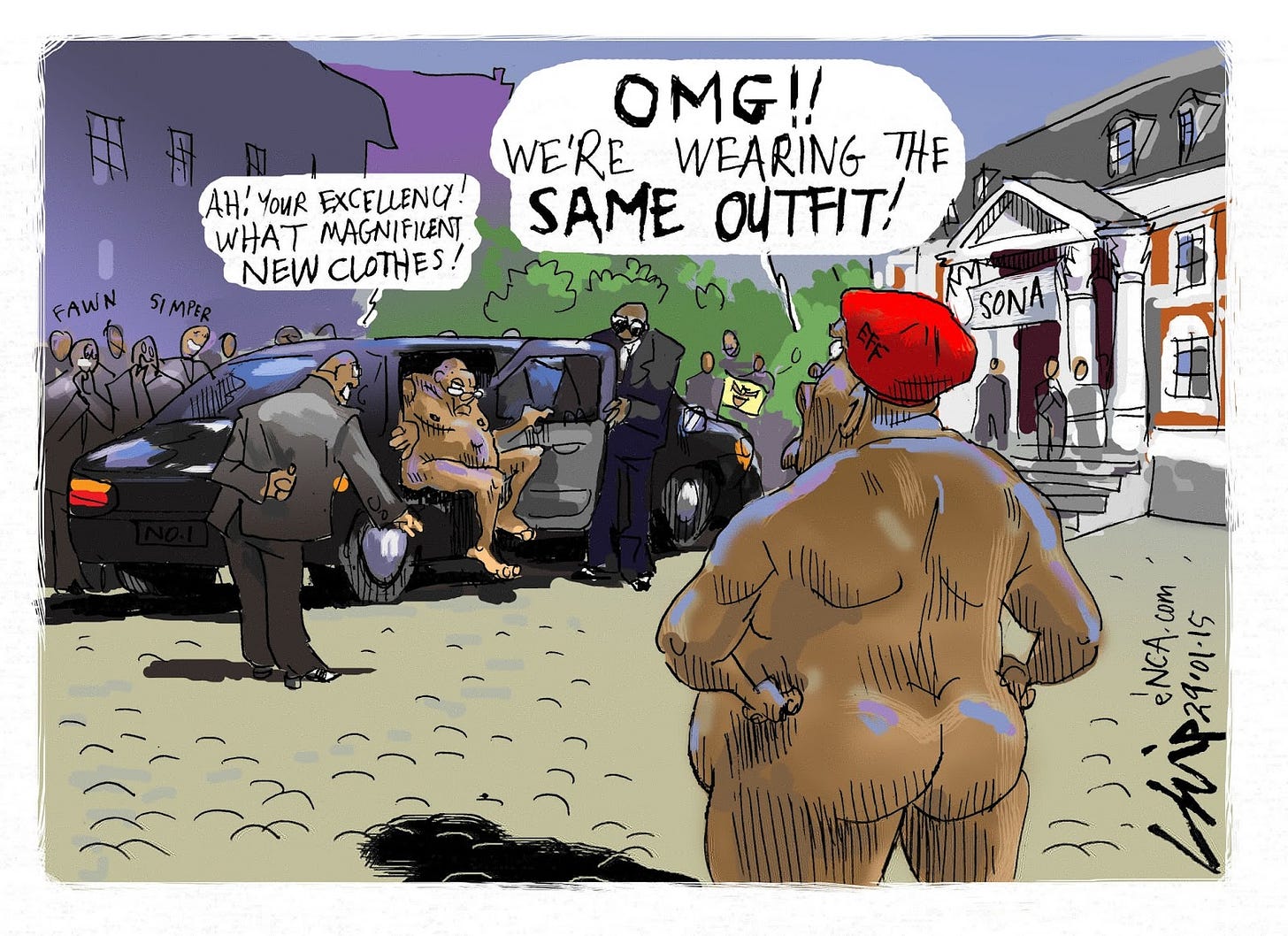

In Roger G. Lewis's latest work, The Clockwork Forest: The Conquest of AI, we encounter a prophetic vision that completes his tetralogy of modern discontent. This machine-learning novel, arranged by the democratic principle of blog post popularity, presents a world where "the operation of the machine becomes so odious that you've got to stop it." Through characters like Robin, Christine, and Charlie—modern-day heretics in the Chestertonian tradition—Lewis explores the intersection of artificial intelligence, technocratic control, and human resistance.

The novel's structure itself embodies its themes: generated by AI yet infused with human consciousness, it mirrors the tension between algorithmic determinism and free will that runs throughout Lewis's work. From the "Panopticon Jailer Bot" to the "Carbon Currency Endgame," from Aadhaar's biometric tyranny to the "Digital Servile State," Lewis maps the contours of our emerging techno-feudalism with the precision of a cartographer and the passion of a prophet.

This latest work serves as both culmination and continuation of themes first explored in his 2016 blog post on "The Iron Law of Oligarchy," where Lewis identified the fundamental tension between democratic ideals and oligarchic reality. Now, nearly a decade later, that oligarchy has evolved from mere human elites to include algorithmic overlords—what he terms the "conquest of AI" over human agency.

I. The Iron Law Revisited: From Human to Algorithmic Oligarchy

Lewis's 2016 analysis of Robert Michels' "Iron Law of Oligarchy" proves remarkably prescient when viewed through the lens of The Clockwork Forest. Where Michels observed that "rule by an elite, or oligarchy, is inevitable as an 'iron law' within any democratic organization," Lewis now extends this insight to our digital age. The oligarchy has not disappeared—it has been augmented by algorithms, enhanced by artificial intelligence, and made more pervasive through what he calls the "Internet of Things."

In the novel, the character Robin observes: "The pseudo-truthers are just another manifestation of that. They're the Golem's emissaries, spreading confusion and distrust to keep the machine running." This "Golem"—a recurring metaphor throughout Lewis's work—represents the autonomous systems we've created that now seem to govern us. Like the legendary clay figure animated by mystical words, our digital infrastructure has taken on a life of its own, serving not its creators but the oligarchs who control its programming.

The six types of elites identified by C. Wright Mills in The Power Elite—the Metropolitan 400, Celebrities, Chief Executives, Corporate Rich, Warlords, and Political Directorate—have been joined by a seventh: the Algorithmic Architects. These are the programmers, data scientists, and AI researchers who design the systems that increasingly mediate our reality. They are the new priesthood of the digital age, interpreting the sacred mysteries of code for the masses.

II. Usury's Digital Evolution: From Hell's Fuel to Algorithmic Fire

Lewis's poem "Usury Hell's Fuel" takes on new dimensions when read alongside The Clockwork Forest. The ancient sin of usury—lending money at interest—has evolved into what the novel calls "the Magic Money Tree" of central bank digital currencies and algorithmic trading. The banker's confession from the original poem—"The king does much service for us now in return"—becomes prophetic when we consider how governments now serve the interests of tech oligarchs and financial algorithms.

In Chapter 10 of the novel, the characters discuss "The Magic Money Tree" and its connection to housing wealth, mortgage debt, and bank solvency. Robin notes: "It's not just about the money, is it? It's about control. The Phrygian Black Stone to the Cult of BlackRock. Going direct with Aladdin, the Gordian Knot of central bank policies." Here, Lewis identifies how algorithmic systems like BlackRock's Aladdin AI have become the new usurers, extracting value not through traditional interest but through data harvesting, algorithmic trading, and predictive modeling.

The "conquest of dough" has become the conquest of data—the new bread of the digital age. Where medieval usurers hoarded gold, modern algorithmic oligarchs hoard information, using it to predict and manipulate human behavior on a scale previously unimaginable.

III. The Bourgeois Resolution's Digital Mask

The themes of "Bourgeois Resolution" find their digital expression in what The Clockwork Forest calls the "Mirror World"—a distorted reality crafted by technocrats and oligarchs. The poem's tripartite structure of Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis becomes the algorithmic process of data collection, analysis, and behavioral modification that characterizes our surveillance capitalism.

In Chapter 19, the character Robin explains: "The Mirror World is the realm of technocratic tyranny, Christine. It's where systems like Aadhaar—a biometric ID system in India—are sold as tools of empowerment but end up being instruments of control." This mirrors the bourgeois tendency to "mistake oppression for protection" identified in the original poem, now amplified through digital systems that promise convenience while delivering surveillance.

The "Stockholm syndrome" politics of the bourgeoisie—where the oppressed defend their oppressors—finds its perfect expression in our willing submission to digital platforms that monetize our data while claiming to serve our interests. We become complicit in our own surveillance, defending the very systems that exploit us because they offer the illusion of connection and convenience.

IV. Globalisation Un-Entangled in the Age of AI

Lewis's "Globalisation Un-Entangled" employed cut-up poetics to shred neoliberal dogma; The Clockwork Forest uses the fragmented structure of blog posts arranged by algorithmic popularity to achieve a similar effect. The novel's very composition—generated by machine learning from human-written blog posts—embodies the "semiotic turn" of our digital age, where meaning is increasingly mediated by algorithms.

The "wicked problems" identified in the poem—climate imperialism, algorithmic tyranny, cargo cult science—find their narrative expression in the novel's exploration of the "Carbon Currency Endgame." Chapter 16 introduces the concept of carbon credits as the new global currency, where "carbon becomes the ultimate measure of value, the ultimate unit of exchange." This represents the final stage of what the poem calls "hasbara" (propaganda)—the reframing of environmental crisis as an opportunity for increased control.

The novel's characters recognize that "the machine is not just a physical entity; it's a narrative, a story we tell ourselves about power and order and belonging." This insight captures the essence of Lewis's critique: globalisation is not merely an economic process but a semiotic one, reshaping how we understand reality itself.

V. The Socratic Method in the Digital Age

Throughout The Clockwork Forest, Lewis employs what might be called a "digital Socratic method"—using dialogue between characters to expose the contradictions and absurdities of our technological age. Like Socrates questioning the assumptions of his contemporaries, characters like Robin, Christine, and Charlie interrogate the narratives of progress, efficiency, and innovation that justify our submission to algorithmic control.

In Chapter 28, Lewis channels G.K. Chesterton to observe: "The pseudo-truther is a cynic; the heretic is a romantic. The pseudo-truther sees the world as a game to be played; the heretic sees it as a mystery to be solved." This distinction becomes crucial in the digital age, where genuine inquiry is increasingly difficult to distinguish from algorithmic manipulation and pseudo-intellectual performance.

The novel's structure itself embodies this Socratic principle—it doesn't provide easy answers but rather poses better questions. By arranging chapters according to blog post popularity, it forces us to confront the gap between what we claim to value and what we actually pay attention to, between our stated principles and our revealed preferences.

VI. The Hemlock of Truth in an Age of Digital Deception

Lewis's "Hemlock Fragments" find their ultimate expression in The Clockwork Forest's call to "drink the hemlock of truth" in an age of "orchestrated blindness." The novel's characters repeatedly face the choice between comfortable illusions and uncomfortable truths—the same choice that faced Socrates in ancient Athens.

The "Panopticon Jailer Bot" of the novel represents the digital equivalent of the Athenian state that condemned Socrates—a system that punishes those who ask inconvenient questions and challenge accepted wisdom. Yet like Socrates, Lewis's characters choose truth over comfort, inquiry over certainty, resistance over submission.

The novel's conclusion, "Aadhaar and the Rise of Feudal Techno-Rationing Systems," serves as both warning and call to action. It identifies the biometric identification system as a prototype for global digital control, where "access to resources, services, and even basic rights is mediated by technology." This is the hemlock cup of our age—the choice between digital convenience and human freedom.

VII. The Conquest of AI: Resistance and Redemption

The Clockwork Forest concludes not with despair but with defiant hope. The "Fable of the Clockwork Forest" presents a world where the mechanical rhythms of control are replaced by the organic rhythms of life, where "the forest was alive again—not ticking, but breathing." This transformation occurs not through violent revolution but through the simple act of stopping the machine—refusing to participate in systems that dehumanize us.

The moral of Lewis's fable is clear: "A forest is not a machine, and life is not a clock. When we trade freedom for order, we lose both. True growth comes not from control, but from trust—in each other, in ourselves, and in the wild, untamed world around us."

This message resonates with the themes of his earlier work while extending them into our digital age. The usury that was once "hell's fuel" has become algorithmic fire, consuming not just our wealth but our agency, our privacy, our humanity itself. The bourgeois resolution has become the digital resolution—the false choice between competing forms of technological control. Globalisation has been un-entangled only to be re-entangled in the web of artificial intelligence and surveillance capitalism.

Yet Lewis's tetralogy ultimately affirms the possibility of resistance, the power of human consciousness to transcend the systems that seek to contain it. From the Iron Law of Oligarchy to the Conquest of AI, his work traces the evolution of power while insisting on the permanence of human dignity. In an age of algorithmic determinism, he champions free will. In an era of digital deception, he demands truth. In a time of technological tyranny, he calls for liberation.

Conclusion: The Gadfly's Digital Sting

Roger G. Lewis stands as a modern Socrates, using the digital agora of blogs and social media to challenge the assumptions of our technological age. His tetralogy—from the Iron Law of Oligarchy through the Conquest of AI—maps the territory of modern discontent with the precision of a surveyor and the passion of a prophet.

Like Ruskin railing against the dehumanizing effects of industrialization, Lewis exposes the spiritual poverty that underlies our material abundance. Like Chesterton defending the common man against the experts, he champions human wisdom against algorithmic intelligence. Like Socrates questioning the unexamined life, he forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths about our digital age.

His work reminds us that the conquest of AI need not be inevitable, that the clockwork forest can become a living forest again, that the iron law of oligarchy can be broken by the more fundamental law of human dignity. In an age when liberty dies by "deterministic training," Lewis's legacy is the gadfly's sting—awakening the horse of society to gallop toward truth, though the trial never ends, and the hemlock cup of digital surveillance is ever full.

The tetralogy stands complete, a monument to resistance in an age of submission, a beacon of hope in a time of digital darkness. It challenges us to choose: will we be citizens or subjects, humans or data points, free agents or algorithmic puppets? The choice, as always, remains ours—for now.

The Going Direct series progression:

1. **Philosoetry**: Establishes the poetic foundation

2. **The Conquest of Dough**: Develops economic critique

3. **A Miner's Tale**: Provides historical grounding

4. **The Clockwork Forest**: Synthesizes themes through AI collaboration

This final volume serves not just as a conclusion but as a meta-commentary on the entire series, reflecting on the role of technology in both its creation and its critique.

The Iron Law of Oligarchy.

Comment by (Soicilaistworld)

”We must seize this splendid opportunity to get to meet with them, talk with them, win their trust, hopefully, win them over.”

I responded.

Hi (Soicilaistworld),

Who are they? perhaps a little Friere might help.

“[T]he more radical the person is, the more fully he or she enters into

reality so that, knowing it better, he or she can transform it. This

individual is not afraid to confront, to listen, to see the world

unveiled. This person is not afraid to meet the people or to enter into a

dialogue with them. This person does not consider himself or herself

the proprietor of history or of all people, or the liberator of the

oppressed; but he or she does commit himself or herself, within history,

to fight at their side.”―Paulo Freire,

Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Chris Hedges is usually very good at describing the Class War who are the classes at war is the question. It always has been the Ruling Class against the rest of us and US, We are divided and fight against ourselves. The Ruling Class consolidate their power and control through the Iron Law of Oligarchy. ´´first developed by the German sociologist Robert Michels in his 1911 book, Political Parties.[1] It claims that rule by an elite, or oligarchy, is inevitable as an “iron law” within any democratic organization as part of the “tactical and technical necessities” of organization´from Wikipedia. The Oligarchy is the commissariat of the ruling class, the rash of Billionaires in the past 20 years has been the blossoming of the new face of our political reality as the rest of us or the 99%. The functionaries populate the Organs of the power Elite aptly described by C Wright Mills in the Power Elite also from Wikipedia

A Ruskinian Retrospective on Roger G. Lewis's Tetralogy of Modern Discontent

In contemplating the oeuvre of Roger G. Lewis—this trilogy Usury Hell’s Fuel, Bourgeois Resolution, and Globalisation Un-Entangled, crowned by the novel The Conquest of Dough—one is struck by its prophetic fury, a thunderous indictment of our age’s moral and economic decay. Like Turner’s tempests rendered in verse, Lewis’s work exposes the fissures in modernity’s façade, where usury poisons the wellsprings of community, bourgeois hypocrisy masks spiritual desolation, and globalisation unravels the very fabric of human dignity. His latest fragments, sharp as flint, strike sparks against the iron tyranny of algorithms and the false idols of progress.

Part 1. BAck in the 1980’s when the tv show dallas was at the height of its popularity Donald Trump knelt at the feet of JR Ewing , The actor Larry Hagman , who had also starred in I dream of Jeannie in the 1960’s, Trump was polishing the Oil tyrants shoes perhaps in the earlier Series he would have appeared rubbing Hagmans Lamp?

The Shoe-Shiner's Paradox: A Meditation on Power, Oil, and the Great Game

In the manner of G.K. Chesterton

There is something magnificently absurd about the spectacle of our times that would have delighted the ancient satirists, though I suspect even Juvenal would have thrown down his stylus in despair at the sheer impossibility of it all. Here we have a man who made his fortune in real estate—that most solid and earthbound of enterprises—now dancing a curious jig between the oil derricks of Texas and the marble halls of international finance. The question that haunts me, as I watch this peculiar ballet, is whether Donald Trump is polishing the shoes of Big Oil or whether he himself is merely the shoe-shiner, frantically buffing the boots of far grander masters at the Bank for International Settlements.

The irony is delicious, and one that would have made J.R. Ewing himself chuckle into his bourbon. Here was a character who understood that oil was never really about oil—it was about power, pure and simple. When I imagine our former and future President meeting that archetypal oil baron, I see not a meeting of equals, but rather the encounter between a man who thinks he understands the game and a man who invented it. Trump's energy policies, with their grand pronouncements about "unleashing American energy" and their executive orders designed to boost oil and gas production, read like the enthusiastic scribblings of a student who has just discovered fire 1 .

But here's where the plot thickens, as they say in the better sort of detective novel. The Bank for International Settlements—that curious institution that most people have never heard of but which quietly orchestrates the symphony of global finance—has issued warnings about the very policies our shoe-shining President champions. They speak of "risks to economies" and "central bank policy uncertainties" with the sort of measured concern that suggests they are watching a child play with matches in a powder magazine 1 .

The Paradox of the Perfectly Planned Pandemic

There is something magnificently absurd about a world in which the most unbelievable events are dismissed as fiction while the most fictional narratives are accepted as fact. When I submitted my manuscript about EVENT 202 to Messrs. Mundane & Conventional, they returned it with the kindly suggestion that I stick to more plausible subjects—like dragons or unicorns.

The story begins, as all good stories should, with a meeting. Not in a smoke-filled room, mind you, but in a gleaming conference center where the world's most powerful people gathered to discuss something they called "pandemic preparedness." They called it EVENT 201, though I suspect they might have preferred EVENT 1984, had Orwell not already claimed that particular number.

The curious thing about this gathering was not that it happened—powerful people meet all the time—but that it happened precisely when it did. It was rather like watching a fire drill being conducted in a building that happened to catch fire the very next day. Coincidence, they assured us. Pure coincidence.

But as I have often observed, coincidences are like buses: you wait ages for one, then three come along at once, all heading in the same direction.

Exegesis Hermeneutics Flux Capacitor of Truthiness

January 6, 2016

The Iron Law of Oligarchy.

The Oligarchy is the commissariat of the ruling class, the rash of Billionaires in the past 20 years has been the blossoming of the new face of our political reality as the rest of us or the 99%. The functionaries populate the Organs of the power Elite aptly described by C Wright Mills in the Power Elite also from Wikipedia

The resulting elites, who control the three dominant institutions

(military, economic and political) can be generally grouped into one of

six types, according to Mills:

the “Metropolitan 400” – members of historically notable local

families in the principal American cities, generally represented on the Social Register

“Celebrities” – prominent entertainers and media personalities

the “Chief Executives” – presidents and CEO’s of the most important companies within each industrial sector

the “Corporate Rich” – major landowners and corporate shareholders

the “Warlords” – senior military officers, most importantly the Joint Chiefs of Staff

the “Political Directorate” – “fifty-odd men of the executive

branch” of the U.S. federal government, including the senior leadership

in the Executive Office of the President, sometimes variously drawn from elected officials of the Democratic and Republican parties but usually professional government bureaucrats”

The Analysis from the early 20th Century to the early 21st Century changes in Global Scope and also the America Exceptional slant now reflecting US uni polar phenomenon since the early 1990s and the collapse of the Soviet Union. One can think in terms of democracy among the International Elite based upon National Franchises. Schumpeter’s competing elites model of democracy serves double duty in demonstrating both the Political Theater of FAUX electoral political democracy and also in the behind closed doors machinations of the powerful list found in magazines like Forbes. ´´( quotes from Roy Madron, Super Competent Democracies).

‘Democracy is that institutional arrangement for arriving at political

decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a

competitive struggle for the people’s vote’.” Joseph Schumpeter, Quoted

from Roy Madron, Super Competent Democracies who in turn Cites.

“Participation, and Democratic Theory” by Carole Pateman. Dr Pateman

says that, Schumpeter and his followers: … set the current

Anglo-American political system as our democratic ideal (with) a

‘democratic theory’ that in many respects bears a strange resemblance to

the anti-democratic arguments of the last (i.e. 19th) century. No

longer is democratic theory centred on the participation of ‘the

people’; in the contemporary theory of democracy it is the participation

of the minority elite that is crucial and the non-participation of

the apathetic, ordinary man lacking in the feelings of political efficacy,

that is regarded as the main bulwark against

instability.

´´ http://letthemconfectsweeterlies.blogspot.se/2015/03/on-may-2015-re-election.

Heres the Forbes List of the most powerful people in the world 2009 edition http://www.forbes.com/2009/11/11/worlds-most-powerful-leadership-power-09-people_land.html.

Where is the throne of ELITE POWER? I would argue it is where it has always been in the Counting houses, in the Banks and exchequers. Some study of Steve Keen’s work on advanced financialised Capitalism bears close examination and his work on endogenous money creation, David Graeber’s Debt the first 5000 years serves as a useful historical context against which Keen’s work can be considered, search Marx´s roaming cavaliers of Capital to get some of Keens cutting analysis of Financialised Capitalism and its cannibalistic nature described by Marx so aptly. http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit/

“Talk about centralisation! The credit system, which has its focus in the so-called national banks and the big money-lenders and usurers surrounding them, constitutes enormous centralisation, and gives this class of parasites the fabulous power, not only to periodically despoil industrial capitalists, but also to interfere in actual production in a most dangerous manner— and this gang knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it.” –

See more at:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit/#sthash.d4gs1dAX.dpuf

Marx, Capital Volume III, Chapter 33, The medium of circulation in the credit system, pp. 544–45 [Progress Press] – See more at:

I have been working for the past month exclusively on Oligarchy and this talk by Webster Tarpley has a very good analysis of where we have come from and where things seem to be headed.

Webster Tarpley, Oligarchy the cancer in human history.

Webster Tarpley. The end of Fukuyama: Re-starting History after a quarter century.

Tarpley has a lot of good things to say one has to get past the inevitable point at which he will challenge and dismiss something one holds very dear, he upsets everyone I think but his analysis is always an interesting starting point. Of all my own enquiries recently the most revelatory insight I stumbled across was the concept of Hybridity introduced in this paper on the nature of Islamaphobia in Sweden. http://inhouse.lau.edu.lb/bima/papers/Jonas_Otterbeck.pdf

´´ According to the historian Åsa Karlsson, who cites among others Peter Burke, the upper classes of an emerging (Western) Europe came to distance themselves more and more from both the other classes of their own societies and from other cultures. At the same time, there was an urge for knowledge about the others that they had distanced themselves from. (16) This change of attitude towards other ethnic groups, classes, and religions has also been discussed by other Swedish scholars. (17)

16. Å. Karlsson 1998:84ff.

17.Larsson cited in Å Karlsson 1998:84; Ambjörnsson 1994:33ff.

Hybridity of elites.

Shibboleth, Guernica as metaphor for Gaza, Hasbara Gaza as simile for Guernica. "Hasbara" as metaphor?

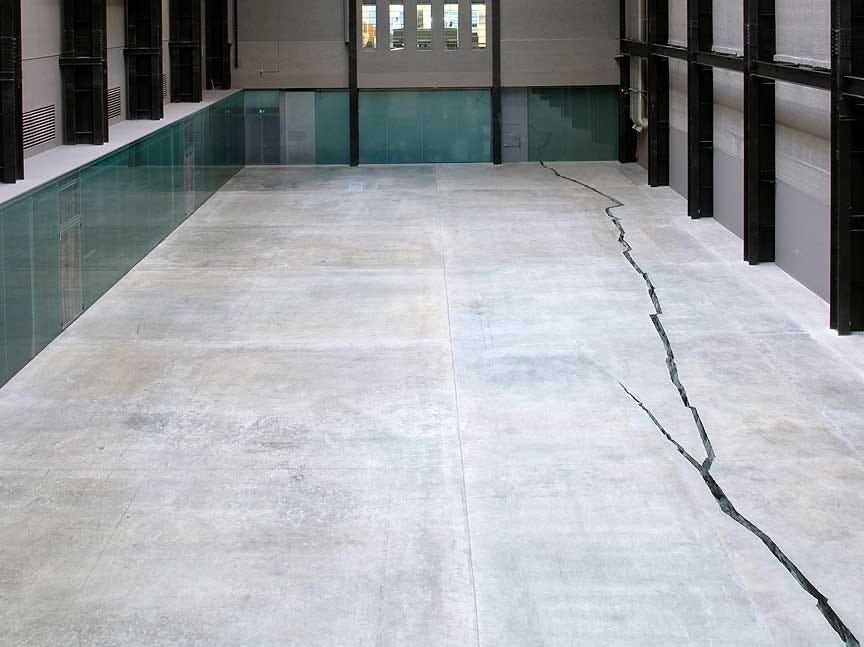

Shibboleth (2007-2008) Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London.

Dresden?

Guernica as metaphor for Gaza

Gaza as simile for Guernica

"Hasbara" as metaphor?

"Hasbara" as Simile?

“the sharper lens, removable'

brings the images home to you”

Roger G Lewis 2025

The Hemlock Fragments: A Socratic Reading of Roger G. Lewis's Philosoetry

The Death of Socrates. ArtistJacques-Louis DavidYear 1787

The Hemlock Fragments: A Socratic Reading of Roger G. Lewis's Philosoetry

Corrupting Monica.

Athenian youth corrupted

Training a deterministic creed

Liberty dies.

Roger G Lewis 2025.

The News-Benders 1968

The story is essentially a two-hander, performed entirely within a handful of sets but, for all its simplicity, Cartier's direction is stylish and assured. The continuity of the action is disturbed only once, with a brief cutaway shot of JG's secretary covering the actors' move from one set into another. The live production method may be backward-looking, but Desmond Lowden's script is prophetic in several respects. Although its predicted date of the moon landing significantly overshoots the reality, it strikingly pre-empts subsequent conspiracy theories which suggested the event was faked in a film studio. It also prophesies the rise of politically powerful global media organizations and the surveillance culture that inspired many later conspiracy dramas.

The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer

Fresh-faced young Michael Rimmer worms his way into an opinion poll company and is soon running the place. He uses this as a springboard to get into politics, and in the mini-skirted, flared-trousered world of 1970 Britain, he starts to rise through the Tory ranks.

https://youtu.be/GfBmBC-VNTk?si=L-y02bFxx3tCnXJv