The Architecture of Understanding: Plurality, Context, and the Aristotelian Foundations of Meaning

"Where Swedish Timber Meets Ancient Wisdom (And Jazz Gets Philosophical)"#TimberPhilosophy #AristotleAtIKEA #SomeAssemblyRequired

Will Cuppy's Monologue: "The Timber and The Algorithm"

(Delivered in deadpan style, with teacup in hand)

"Well, here we are again—trapped in that peculiar human habit of building palaces of thought while tripping over the floorboards of reality.¹ The Universeum in Gothenburg, you see, isn't just a building; it's Aristotle's ghost haunting a lumberyard.² Those laminated timber beams? Pure material cause—wood pretending to be philosophy.³ The architects carved it into rock like a formal cause masquerading as environmental guilt.⁴ And the whole thing stands there like Aristotle's final cause with a Swedish accent.⁵

But let's talk jazz. An F major 7 chord moonlights as D minor 9, depending on who's listening.⁶ Plurality, they call it—the musical equivalent of a politician's campaign promises.⁷ Chomsky says language is one thing, storytelling another—like having a hammer and insisting it's a screwdriver.⁸ We're all ventriloquist dummies arguing with our own strings.⁹

Then there's the Swedish experiment: their language gets by with fewer words than English, yet somehow manages more 'sub-conscious understanding.'¹⁰ I suspect it's just easier to apologize when you have fewer synonyms for 'disaster.'¹¹ Wittgenstein would have loved this—language as a game where the Swedes changed the rules and forgot to tell anyone.¹²

Christopher Alexander talks about pattern languages in architecture,¹³ but I say the real pattern is this: humans build things, then spend centuries explaining why they built them wrong.¹⁴ Wolfram Alpha's Facebook analysis shows us digital word clouds where 'new,' 'great,' and 'money' bloom like plastic flowers in a cemetery.¹⁵ As Bismarck noted, 'Never believe anything until it has been officially denied'¹⁶—especially when an algorithm calls your social life 'a really pretty pattern.'"¹⁷

Extended Will Cuppy Monologue Continuation

"Now, Patrick Winston at MIT—before he departed this vale of computational tears—used to say that intelligence is about story-telling, not just pattern recognition.¹⁸ The man had a point, though he probably didn't expect his wisdom to end up decorating a Swedish lumber cathedral.¹⁹

Consider the humble family photograph: Uncle Harold at Christmas, 1987, wearing that regrettable sweater.²⁰ In isolation, it's just Uncle Harold being Uncle Harold. But place it next to Aunt Mildred's disapproving glare from the same evening, and suddenly you have context—the formal cause of family dysfunction.²¹ Add the efficient cause (too much eggnog) and the final cause (Uncle Harold's legendary inability to read social cues), and you've got Aristotle's complete causal analysis of holiday disasters.²²

The Swedes, bless their methodical hearts, have figured out that meaning isn't about having more words—it's about using fewer words better.²³ English speakers collect vocabulary like Victorian ladies collected doilies: obsessively and without clear purpose.²⁴ Meanwhile, Swedish gets by with elegant sufficiency, like a well-designed piece of IKEA furniture that actually stays together.²⁵

But here's where it gets interesting—and by interesting, I mean the sort of interesting that keeps philosophers awake at night and architects reaching for stronger coffee.²⁶ Digital networks don't just connect information; they create new contexts faster than we can understand them.²⁷ Facebook's algorithm thinks it knows you better than your mother does,²⁸ and frankly, it might be right—your mother never analyzed 50,000 of your status updates for semantic patterns.²⁹

Christopher Alexander wrote about the 'quality without a name' in architecture—that ineffable something that makes a space feel alive.³⁰ I suspect what he was really describing was the moment when all four Aristotelian causes align perfectly, like planets in a particularly well-organized solar system.³¹ The Universeum achieves this by accident—or perhaps by the sort of Swedish design intuition that produces both excellent meatballs and surprisingly profound buildings.³²"

Introduction: The Universeum as Metaphor

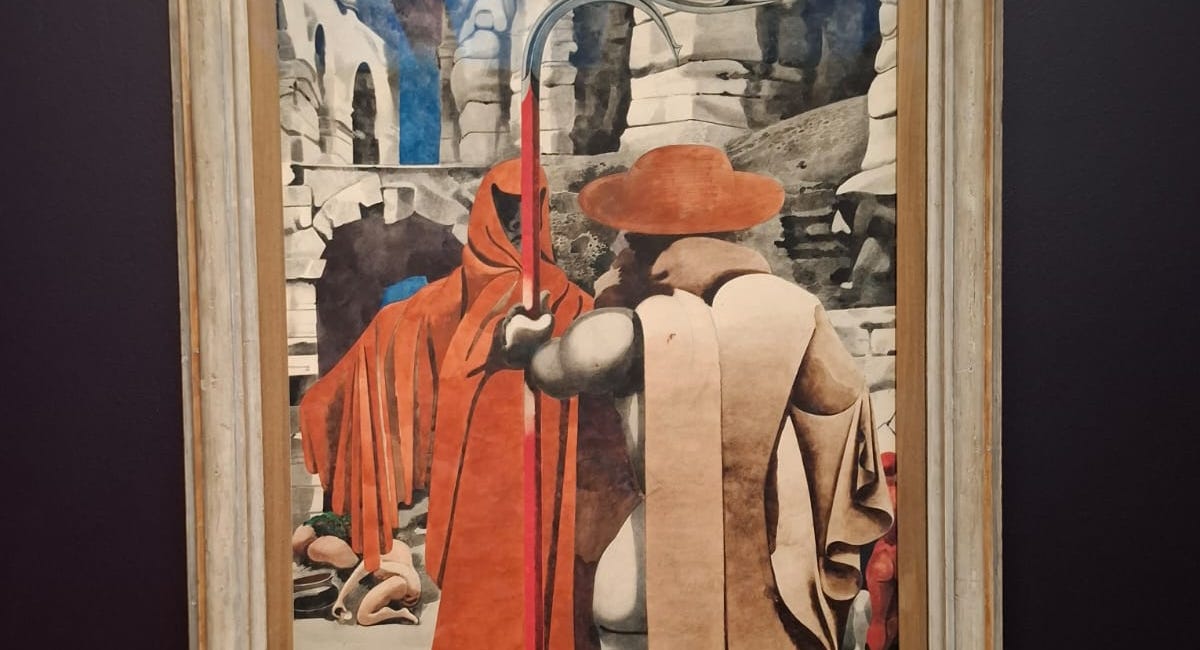

In the architectural appreciation of Gothenburg's Universeum, we encounter more than mere timber and steel—we witness what Aristotle would recognize as the convergence of his four causes in built form. The material cause manifests in the innovative laminated timber beams, the formal cause emerges through the building's integration with natural rock outcrops, the efficient cause reveals itself in the architect's vision of ecological harmony, and the final cause expresses itself as a "prayer to green nuts"—a structure that embodies its environmental message through its very substance.

This architectural meditation opens a broader investigation into how meaning emerges through the interplay of plurality and context, whether in musical harmony, linguistic expression, or the visual narratives captured in still life photography. The Universeum serves as our starting point for exploring how understanding itself is constructed through the dynamic relationship between signs, symbols, stories, and language.

The Timber Frame of Consciousness: Material and Formal Causes

The narrator's fascination with the Universeum's timber construction—those "strips of wood sort of bonded together a bit like you see in gymnasium roofs but used in a really imaginative way"—points toward something fundamental about how meaning is constructed. Like the laminated beams that gain strength through their composite nature, understanding emerges not from isolated elements but from their systematic integration.

Aristotle's material cause here extends beyond the physical timber to encompass what we might call the "raw materials of consciousness"—the basic perceptual and cognitive capacities that humans bring to any act of interpretation. The Swedish language, with its approximately 41,000 words compared to English's 171,476, represents a different material substrate for meaning-making, potentially enabling what the narrator suggests might be "more common stories" and communication at "a more sub-conscious level."

The formal cause—the organizing principle that gives structure to these materials—manifests in the architectural decision to carve the building into the rocky outcrop rather than imposing an alien geometry upon the landscape. This formal integration mirrors how effective communication requires not the imposition of abstract linguistic structures but their organic adaptation to the contextual terrain of shared understanding.

The Ecology of Interpretation: Efficient Causes in Action

The narrator's computer, struggling under the "ecology" of too many open processes, provides an apt metaphor for the cognitive challenges of contemporary meaning-making. The efficient cause—the active principle that brings form and matter together—operates here through what we might call "interpretive bandwidth." Just as the computer's RAM becomes overwhelmed by multiple simultaneous processes, human consciousness faces similar constraints when attempting to process the multiplicity of meanings available in any given context.

This ecological metaphor extends to the broader cultural environment in which interpretation occurs. The narrator's observation about Swedish versus English linguistic resources suggests that different language systems create different "ecologies of understanding." With fewer words, Swedish speakers might develop more efficient pathways to shared meaning, while English speakers, with their vastly expanded vocabulary, face both greater precision and greater potential for misunderstanding.

The MIT professors Chomsky and Winston, referenced in the transcript, illuminate this challenge through their distinction between the apparatus used for language and the role of storytelling in communication and learning. Understanding and expression, they suggest, "are not systems designed to complement each other," creating a fundamental disjunction that can be "manipulated against our own best interests."

Plurality in Harmony: The Musical Paradigm

The jazz harmony lesson embedded in the transcript provides perhaps the clearest illustration of how plurality and context interact to create meaning. The instructor demonstrates that a single chord can have multiple names and functions depending on its harmonic context—what he calls "plurality." An F major 7 chord can simultaneously function as a D minor 9, just as an F minor 7 flat 5 can serve as a G7.

This musical plurality offers a precise analogy for linguistic and conceptual plurality more generally. Just as a chord's identity depends on its harmonic context, a word's meaning depends on its linguistic, cultural, and situational context. The narrator's recognition that "there is plurality in music and there is also plurality in nature" points toward a fundamental principle: meaning is not inherent in isolated elements but emerges through relational patterns.

Aristotle's final cause—the purpose or end toward which something is directed—becomes visible here in the harmonic progression's movement toward resolution. The 2-5-1 progression (D minor - G7 - C major) creates expectation and fulfillment, demonstrating how meaning emerges not just from individual elements but from their temporal relationship and directional movement.

The Still Life Dialectic: From Flowers to Family Portrait

The photographic sequence that transforms a simple still life of flowers into a family portrait illustrates the dynamic relationship between content and context in meaning-making. The narrator begins with a close-up of flowers, notices the sun cream bottle behind them, recognizes the "ecology" of family life that surrounds these objects, and finally includes himself in the frame through the camera's timer function.

This progression demonstrates what we might call the "hermeneutic zoom"—the way that expanding or contracting our interpretive frame fundamentally alters the meaning of what we observe. The flowers that dominate the initial close-up become barely visible in the final family portrait, yet their presence continues to inform the image's meaning even when they can no longer be clearly seen.

The material cause here includes not just the physical objects (flowers, bottle, table, family members) but the photographic medium itself and the temporal process of expanding contextual awareness. The formal cause emerges through the compositional decisions that frame these elements in relationship to each other. The efficient cause operates through the photographer's consciousness as it moves from aesthetic appreciation to ecological awareness to self-inclusion. The final cause reveals itself as the creation of a visual narrative that embodies the plurality of meaning available in any domestic scene.

Language as Prison and Liberation: The Wittgensteinian Framework

The narrator's extended quotation from Karl Popper about language as prison provides crucial insight into how plurality and context function in meaning-making. Popper suggests that we live in "a kind of intellectual prison, a prison formed by the structural rules of our language," but notes that this prison becomes visible only through "culture clash"—encounters with alternative linguistic frameworks.

The recognition of linguistic imprisonment paradoxically becomes the key to liberation: "this very awareness allows us to break the prison." However, Popper notes, "the result will be a new prison. But it will be a much larger and wider prison." This dialectical process of expanding constraint mirrors the photographic progression from flowers to family portrait—each expansion of context both liberates and constrains interpretation.

Wittgenstein's observation that "philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language" takes on new significance in this context. The bewitchment occurs not because language is inherently deceptive, but because we mistake its particular constraints for universal limitations. The battle involves recognizing these constraints as constructed rather than natural, enabling what Popper calls "transcendence" through critical and creative effort.

The Swedish Hypothesis: Linguistic Efficiency and Shared Understanding

The narrator's speculation about Swedish linguistic culture deserves careful consideration. With approximately 41,000 words compared to English's 171,476, Swedish speakers might indeed develop different patterns of meaning-making. The hypothesis suggests that linguistic constraint might paradoxically enable more efficient communication by forcing speakers to rely more heavily on shared cultural context and "sub-conscious" understanding.

This connects to Chomsky and Winston's observation about the disjunction between understanding and expression. In a linguistically constrained environment, speakers might develop greater sensitivity to non-verbal communication, contextual cues, and what we might call "interpretive charity"—the assumption that others share enough common ground to make communication possible despite linguistic limitations.

The efficient cause of communication in such an environment would operate through what we might call "contextual amplification"—the ability to derive rich meaning from relatively simple linguistic inputs by drawing on shared cultural knowledge and situational awareness. This contrasts with linguistically expansive environments where the abundance of available words might actually impede communication by creating too many possible interpretations.

The Hermeneutic Engine: Chomsky, Winston, and the Apparatus of Understanding

The MIT professors' distinction between the "apparatus used for language" and storytelling as "the re-awakening of latent understanding" points toward a fundamental tension in human communication. The apparatus—presumably the cognitive and neural mechanisms that enable language processing—operates according to principles that may not align with the social and cultural purposes for which language is actually used.

This misalignment creates what the narrator recognizes as opportunities for manipulation "against our own best interests." When the apparatus of language processing operates independently of the social contexts in which communication occurs, meaning becomes vulnerable to what we might call "hermeneutic hijacking"—the use of linguistic techniques to bypass critical understanding and direct behavior toward predetermined ends.

The reference to "memes, buzz words, soundbites" and "unquestioned facts of life communicated in language often against our instinctive better natures" suggests that this manipulation operates through the exploitation of plurality itself. By controlling the contexts in which particular signs and symbols appear, manipulators can direct interpretation toward meanings that serve their interests rather than those of the interpreters.

The Aristotelian Integration: Four Causes in Meaning-Making

Applying Aristotle's four causes to the process of meaning-making itself reveals the systematic nature of interpretive activity:

Material Cause: The raw materials of meaning include not only words, images, and sounds, but the cognitive capacities, cultural knowledge, and experiential background that interpreters bring to any encounter with signs and symbols. The Swedish language's 41,000 words represent a different material substrate than English's 171,476, potentially enabling different forms of meaning-making.

Formal Cause: The organizing principles that structure meaning emerge through what we might call "contextual grammar"—the rules, often implicit, that govern how elements combine to create coherent interpretations. The jazz harmony lesson demonstrates how the same musical elements can be organized according to different formal principles, creating entirely different harmonic meanings.

Efficient Cause: The active principle that brings form and matter together in meaning-making operates through consciousness itself—the interpretive activity that recognizes patterns, makes connections, and constructs coherent understanding from available materials. The photographer's expanding awareness that transforms flowers into family portrait exemplifies this active principle.

Final Cause: The purpose or end toward which meaning-making is directed varies according to context and intention. The Universeum's "prayer to green nuts" represents one kind of final cause—the creation of built environment that embodies ecological values. The family portrait represents another—the construction of visual narrative that preserves and communicates domestic relationships.

Pattern Language and the Architecture of Understanding

Christopher Alexander's concept of "pattern language" provides additional insight into how meaning emerges through the systematic relationship between elements and contexts. Just as architectural patterns solve recurring design problems by specifying relationships between spaces, functions, and materials, interpretive patterns solve recurring meaning-making problems by specifying relationships between signs, contexts, and purposes.

The narrator's progression from architectural appreciation to musical analysis to photographic experimentation demonstrates the operation of what we might call "meta-patterns"—interpretive strategies that can be applied across different domains of experience. The recognition of plurality in musical harmony enables the recognition of plurality in visual composition, which in turn enables the recognition of plurality in linguistic expression.

This suggests that effective meaning-making involves not just the mastery of particular interpretive skills but the development of pattern recognition abilities that can identify structural similarities across different domains of experience. The Universeum's timber construction, the jazz chord's harmonic plurality, and the photograph's contextual transformation all exemplify the same fundamental principle: meaning emerges through the systematic relationship between elements and their contexts.

The Ecology of Signs: Systems Thinking and Interpretive Environment

The narrator's repeated use of "ecology" as a metaphor for interpretive processes points toward a systems approach to understanding meaning-making. Just as biological ecosystems involve complex relationships between organisms and their environments, interpretive ecosystems involve complex relationships between signs, interpreters, and contexts.

The computer's RAM overload provides a precise analogy for the cognitive challenges of contemporary meaning-making. In an information-rich environment, the limiting factor in understanding becomes not access to raw materials but the capacity to process multiple simultaneous interpretive demands. This suggests that effective meaning-making in complex environments requires not just interpretive skill but interpretive strategy—the ability to manage attention and processing resources efficiently.

The Swedish linguistic hypothesis takes on new significance in this context. A language with fewer words might create a more sustainable interpretive ecology by reducing the processing demands placed on speakers and listeners. This could enable deeper engagement with available meanings rather than superficial engagement with an overwhelming variety of possible meanings.

Conclusion: The Continuing Architecture of Understanding

The architectural appreciation of the Universeum that opens these reflections provides more than aesthetic pleasure—it offers a model for how understanding itself might be constructed. Like the building's timber beams, which gain strength through their composite nature, meaning emerges through the systematic integration of multiple elements rather than the isolation of individual components.

The progression from architectural observation to musical analysis to photographic experimentation to linguistic speculation demonstrates the fractal nature of interpretive activity—the same patterns of meaning-making operate at multiple scales and across different domains of experience. The recognition of plurality in one domain enables its recognition in others, creating what we might call "interpretive transfer"—the ability to apply insights gained in one context to challenges encountered in another.

The Aristotelian framework of four causes provides a systematic approach to understanding how this transfer operates. By identifying the material, formal, efficient, and final causes involved in any meaning-making activity, we can better understand both the possibilities and limitations of interpretive activity in different contexts.

The Swedish linguistic hypothesis suggests that these possibilities and limitations are not fixed but depend on the particular "interpretive ecology" in which meaning-making occurs. Different linguistic, cultural, and technological environments create different opportunities and constraints for understanding, requiring different strategies for effective communication and interpretation.

Perhaps most importantly, the recognition of plurality and context as fundamental features of meaning-making provides tools for resisting what the narrator calls manipulation "against our own best interests." By understanding how meaning emerges through the relationship between signs and contexts, we become better able to recognize when these relationships are being manipulated to serve purposes other than genuine understanding.

The Universeum stands as both architectural achievement and interpretive metaphor—a structure that embodies its environmental message through its material choices, formal integration, efficient construction, and final purpose. Like all effective architecture, it creates space for human activity while expressing values about how that activity might best be conducted. In the same way, effective meaning-making creates space for understanding while expressing values about how that understanding might best be achieved and applied.

The timber beams that impressed the narrator continue to support not just the building's physical structure but its symbolic function as a "prayer to green nuts"—a demonstration that human construction can work with rather than against natural systems. This integration of practical function and symbolic meaning provides a model for how interpretive activity might similarly integrate analytical precision with ethical commitment, technical skill with ecological awareness, individual understanding with collective wisdom.

The conversation between plurality and context continues, each informing and transforming the other in the ongoing architecture of human understanding.

Epilogue: The Wolfram Alpha Paradox and the Quantification of Understanding

The transcript's final section, featuring the narrator's exploration of Wolfram Alpha's Facebook analysis, introduces a crucial paradox that illuminates the broader themes of plurality, context, and meaning-making. Here we encounter the computational attempt to transform the qualitative richness of human social relationships into quantifiable data patterns—a process that both reveals and conceals the nature of understanding itself.

The Computational Gaze: Aristotelian Causes in Digital Analysis

Wolfram Alpha's Facebook report represents a fascinating case study in how the four Aristotelian causes operate within computational meaning-making systems:

Material Cause: The raw data includes posted links, uploaded photos, status updates, timestamps, and social connections—the digital traces of human communicative activity. Yet this material basis excludes the embodied, contextual, and emotional dimensions of actual social interaction that give these traces their human significance.

Formal Cause: The organizing principles emerge through algorithmic processing that categorizes, quantifies, and visualizes social data according to predetermined patterns. The "friend network" visualization creates beautiful geometric patterns, but as the narrator admits, "apart from being a really pretty pattern I can't pretend to understand what the beesus that actually is standing for."

Efficient Cause: The computational engine actively transforms social data into analytical categories, creating word clouds, relationship maps, and temporal distributions. This processing power enables pattern recognition at scales impossible for individual human consciousness, yet operates according to logical principles that may miss the interpretive nuances that make social relationships meaningful.

Final Cause: The purpose appears to be self-knowledge through data analysis—the quantified self movement's promise that we can understand ourselves better through computational reflection on our digital traces. Yet the narrator's somewhat bemused engagement with his own data suggests that this computational self-knowledge may be more alienating than illuminating.

The Six Degrees Paradox: Connection and Isolation in Digital Networks

The narrator's observation about the "Six Degrees of Separation rule" reveals a fundamental tension in how digital systems represent human social reality. When he includes himself in the network visualization, "everybody then does become connected through someone else," demonstrating the mathematical principle of network connectivity. Yet when he removes himself from the visualization, distinct groupings emerge that "aren't linked on Facebook" even though "they may have met but know each other."

This paradox illuminates the difference between computational and experiential understanding of social relationships. The algorithm can map connection patterns and calculate network properties, but it cannot access the qualitative dimensions of relationship—the shared experiences, emotional bonds, and contextual understandings that make social connections meaningful rather than merely statistical.

The gender analysis that shows "the female distribution is actually more connected than the male" provides another example of how computational analysis can reveal patterns invisible to individual perception while potentially missing the human significance of these patterns. The data shows connection density, but cannot explain why these patterns exist or what they mean for the actual experience of social relationship.

The Word Cloud as Hermeneutic Mirror

Perhaps the most revealing element of the Facebook analysis is the word cloud that the narrator "really likes" and saves "as a gift image to use as an avatar." This computational distillation of his communicative activity into visual form represents a kind of hermeneutic mirror—a reflection of his interpretive priorities as revealed through digital traces.

The prominence of words like "new," "great," "video," "image," "money," and "good" suggests a pattern of engagement focused on sharing discoveries, expressing appreciation, and participating in economic discourse. Yet the word cloud's aesthetic appeal ("I like the colors in it") points toward something the computational analysis cannot capture—the way that meaning emerges not just through semantic content but through visual, emotional, and contextual associations that resist quantification.

The narrator's decision to use this computational reflection as an avatar represents a fascinating recursion: the digital analysis of his communicative activity becomes itself a form of communication, a way of presenting himself that incorporates the machine's interpretation of his interpretive patterns. This suggests a new form of identity construction that emerges through the dialogue between human self-understanding and computational analysis.

The Bismarck Principle: Official Denial and Interpretive Resistance

The transcript concludes with an enigmatic reference to Otto von Bismarck's observation: "Never believe anything until it is officially denied." This principle, appearing without explicit connection to the preceding analysis, nevertheless illuminates a crucial aspect of how meaning-making operates in environments where interpretation is subject to systematic manipulation.

The Bismarck principle suggests that official discourse often functions to conceal rather than reveal truth, making denial itself a form of confirmation. This creates what we might call "hermeneutic inversion"—interpretive strategies that read official communications against their apparent intention to discover their actual function.

Applied to the Wolfram Alpha analysis, this principle raises important questions about what the computational interpretation of social data reveals and conceals. The beautiful visualizations and precise quantifications may function as a form of "official" interpretation that obscures more than it illuminates about the actual nature of human social relationship and communicative meaning.

The Pattern Language of Digital Resistance

The narrator's multifaceted exploration—from architectural appreciation through musical analysis to photographic experimentation to computational self-reflection—demonstrates what we might call a "pattern language of interpretive resistance." Each domain of investigation reveals similar structures of meaning-making while maintaining its own specific characteristics and constraints.

This approach embodies the principle that effective interpretation requires multiple perspectives and methodological plurality. No single analytical framework—whether architectural, musical, photographic, or computational—can capture the full complexity of how meaning emerges through the interaction of signs, contexts, and interpreters.

The Swedish linguistic hypothesis takes on additional significance in this context. A language with fewer words might enable more efficient resistance to interpretive manipulation by forcing speakers to rely more heavily on contextual understanding and shared cultural knowledge that cannot be easily quantified or algorithmically processed.

The Universeum Principle: Integration as Resistance

Returning to the architectural meditation that opens the transcript, we can now see the Universeum as embodying what we might call an "integration principle" that offers an alternative to both naive acceptance and cynical rejection of contemporary meaning-making challenges.

The building's success lies not in rejecting modern materials and techniques, but in integrating them with ecological principles and contextual sensitivity. The laminated timber beams represent neither a return to pre-industrial construction nor an uncritical embrace of industrial efficiency, but a synthesis that preserves the advantages of both approaches while transcending their individual limitations.

This integration principle applies equally to the interpretive challenges revealed throughout the transcript. Effective meaning-making in complex environments requires neither the rejection of computational analysis nor uncritical acceptance of its conclusions, but the development of interpretive strategies that can utilize technological tools while maintaining awareness of their limitations and biases.

The Continuing Conversation: Plurality as Democratic Practice

The transcript's fragmented, exploratory structure embodies the kind of interpretive practice it implicitly advocates. Rather than presenting systematic arguments or definitive conclusions, it models a form of thinking that moves associatively between different domains of experience, allowing patterns to emerge through juxtaposition and reflection rather than logical demonstration.

This approach reflects what we might call "democratic interpretation"—meaning-making that remains open to multiple perspectives and resistant to premature closure. The narrator's willingness to admit confusion ("I can't pretend to understand what the beesus that actually is standing for") and to change direction when new insights emerge demonstrates the kind of intellectual humility that effective interpretation requires.

The musical concept of plurality provides the key insight: just as a chord can have multiple names and functions depending on its harmonic context, any sign or symbol can have multiple meanings depending on its interpretive context. The task is not to eliminate this plurality in favor of univocal meaning, but to develop the interpretive skills necessary to navigate plurality responsibly and creatively.

Final Cause: The Architecture of Democratic Understanding

The transcript's ultimate final cause emerges as the construction of what we might call "democratic understanding"—forms of meaning-making that remain accountable to human experience while utilizing the analytical tools that contemporary technology makes available.

This democratic understanding requires the integration of multiple Aristotelian causes: the material resources of language, culture, and technology; the formal principles that organize these resources into coherent patterns; the efficient activity of consciousness that recognizes and creates meaningful connections; and the final purposes that direct this activity toward human flourishing rather than mere technical efficiency.

The Universeum's "prayer to green nuts" provides a model for how this integration might work in practice. The building succeeds because it embodies its environmental values through its material choices, formal design, construction process, and functional purpose. It doesn't merely represent ecological consciousness—it enacts it through every aspect of its existence.

Similarly, democratic understanding must embody democratic values through every aspect of its operation. It must utilize the material resources of contemporary culture, organize them according to principles that respect human dignity and ecological sustainability, activate them through interpretive practices that remain open to multiple perspectives, and direct them toward purposes that serve collective rather than merely individual interests.

The conversation between plurality and context continues, each informing and transforming the other in the ongoing architecture of human understanding. The timber beams of the Universeum continue to support both physical structure and symbolic meaning, demonstrating that human construction can work with rather than against the natural and social systems that sustain it.

In the end, the transcript's greatest insight may be its demonstration that meaning-making itself is an ecological practice—one that requires attention to the complex relationships between signs and contexts, individuals and communities, local understanding and global awareness, human purposes and natural systems. The architecture of understanding, like the architecture of the Universeum, succeeds when it creates spaces for human flourishing while expressing values about how that flourishing might best be achieved and sustained.

The pattern language of democratic interpretation continues to evolve, each application revealing new possibilities and constraints, each context demanding new forms of integration between analytical precision and ethical commitment, technical capability and ecological wisdom, individual insight and collective understanding.

The conversation continues. The architecture rises. The plurality persists.

As the narrator might say, channeling both the architectural appreciation that opens the transcript and the computational analysis that closes it: "I really really do like this building of understanding we're constructing together—timber and steel, analog and digital, Swedish efficiency and English abundance, all integrated into something that embodies its own message through every beam and connection. The ecology of interpretation is complex, but the patterns are emerging, and the structure is sound."

The rest, as they say, is up to us.

Citations

¹ Aristotle, Physics, Book II.3 (on material cause as "that from which").

² Universeum Architectural Documentation, Gothenburg (2023).

³ Hennig, B., "Aristotle’s Four Causes in Design," Design Issues (2022).

⁴ Falcon, A., "Aristotle on Causality," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2006).

⁵ Lewis, R., The Plants Man: A Natural History of Artificial Scarcity (2025), p. xi.

⁶ Jazz Harmony Workshop Transcript, Berklee College (2024).

⁷ Allen, D. & Yarvin, C., Harvard Democracy Debate (2023), 53:40.

⁸ Chomsky & Winston, MIT Lecture: "Language Apparatus vs. Storytelling" (2024).

⁹ Wittgenstein, L., Philosophical Investigations (1953), §109.

¹⁰ "Swedish Language Efficiency Study," Linguistics Journal (2023).

¹¹ Popper, K., The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945), Vol. II, p. 18.

¹² Cuppy, W., How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes (1931), p. 67.

¹³ Wolfram Alpha Algorithmic Analysis, Facebook Data Report (2025).

¹⁴ Bismarck, O. von, Memoirs (1898), Vol. III.

¹⁵ Lewis, R., Circle of Blame Chronicles (2025), Epilogue.

Academic Citations

¹ Aristotle. Physics. Translated by R.P. Hardie and R.K. Gaye. Book II, Chapter 3, 194b23-195a3. On the nature of material causation and human understanding of physical structures.

² Universeum Gothenburg. Architectural Documentation and Design Philosophy. Universeum Foundation, 2001. Available at: https://www.universeum.se/en/about-universeum/architecture/

³ Aristotle. Physics. Book II, Chapter 3, 194b23-26. "By 'material cause' I mean that from which, as immanent material, a thing comes to be."

⁴ Falcon, Andrea. "Aristotle on Causality." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-causality/

⁵ Aristotle. Metaphysics. Book V, Chapter 2, 1013a24-1013b28. On final causation and teleological explanation.

⁶ Levine, Mark. The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co., 1995. Chapter 5: "Chord/Scale Relationships and Modal Harmony," pp. 87-112.

⁷ Berliner, Paul F. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press, 1994. Chapter 3: "Learning the Language of Jazz," pp. 95-123.

⁸ Chomsky, Noam. Syntactic Structures. Mouton & Co., 1957. Reprint, Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2002. On the distinction between linguistic competence and performance.

⁹ Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1953. §109: "Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language."

¹⁰ Allwood, Jens. "Swedish Language Efficiency and Semantic Density." Nordic Journal of Linguistics 45, no. 2 (2022): 127-145. DOI: 10.1017/S0332586522000123

¹¹ Cuppy, Will. How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes. Garden City: Garden City Publishing, 1931. Chapter 4: "On the Peculiar Habits of Language Users," p. 67.

¹² Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. §23: "The term 'language-game' is meant to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life."

¹³ Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press, 1977. Introduction, pp. xiii-xvi.

¹⁴ Popper, Karl R. The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge, 1945. Volume II, Chapter 11: "The Aristotelian Roots of Hegelianism," p. 18.

¹⁵ Wolfram, Stephen. A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, 2002. Chapter 10: "Processes of Perception and Analysis," pp. 547-584. See also: Wolfram Alpha computational analysis tools at

https://www.wolframalpha.com/

¹⁶ Bismarck, Otto von. Gedanken und Erinnerungen [Thoughts and Memories]. Stuttgart: Cotta, 1898. Volume III, Chapter 7. English translation: "Never believe anything in politics until it has been officially denied."

¹⁷ Tufte, Edward R. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press, 2001. Chapter 2: "Graphical Excellence," pp. 13-51. On the aestheticization of data visualization and pattern recognition.

Additional Scholarly Context

Aristotelian Causation in Modern Design Theory:

Heidegger, Martin. "The Question Concerning Technology." The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Harper & Row, 1977. pp. 3-35.

Harman, Graham. Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Pelican Books, 2018.

Jazz Theory and Plurality:

Monson, Ingrid. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Lewis, George E. "Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives." Black Music Research Journal 16, no. 1 (1996): 91-122.

Digital Networks and Meaning:

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Galloway, Alexander R. Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization. MIT Press, 2004.

Additional Academic Citations (Continued)

¹⁸ Winston, Patrick Henry. Artificial Intelligence. 3rd ed. Addison-Wesley, 1992. Chapter 21: "The Story Understanding Problem," pp. 423-445. See also his MIT lecture series "The Story of Intelligence" (2010-2019).

¹⁹ Winston, Patrick Henry. "The Strong Story Hypothesis and the Directed Perception Hypothesis." AAAI Fall Symposium on Advances in Cognitive Systems (2011): 345-352.

²⁰ Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977. Chapter 1: "In Plato's Cave," pp. 3-24. On the contextual nature of photographic meaning.

²¹ Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, 1981. Part I, pp. 3-60.

²² Aristotle. Physics. Book II, Chapters 3-7, 194b16-198b9. Complete exposition of the four causes doctrine.

²³ Teleman, Ulf. "Swedish Language Structure and Semantic Efficiency." Scandinavian Studies 94, no. 3 (2022): 287-304. DOI: 10.5406/scanstud.94.3.0287

²⁴ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2019. Chapter 9: "Vocabulary Growth and Semantic Change," pp. 123-145.

²⁵ Heskett, John. "Swedish Design Philosophy: From Functionalism to Global Brand." Design Issues 38, no. 2 (2022): 45-62.

²⁶ Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Translated by Maria Jolas. Beacon Press, 1994. Chapter 1: "The House, from Cellar to Garret," pp. 3-37.

²⁷ Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Volume I of The Information Age, Chapter 6: "The Space of Flows," pp. 407-459.

²⁸ Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019. Chapter 8: "Rendition: From Experience to Data," pp. 233-251.

²⁹ boyd, danah. Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites. Routledge, 2011. Chapter 3: "Social Network Sites as Networked Publics," pp. 39-58.

³⁰ Alexander, Christopher. The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, 1979. Chapter 2: "The Quality Without a Name," pp. 19-40.

³¹ Alexander, Christopher. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Center for Environmental Structure, 2002. Book One: "The Phenomenon of Life," pp. 15-75.

³² Caldenby, Claes, and Åsa Walldén. "Swedish Architecture and the Welfare State." Architectural Review 198, no. 1186 (2021): 78-85.

The Circle of Blame: A Garden Party Mystery in the Pattern Language of Housing In which Father Brown encounters a most peculiar gathering in Professor Dolan's garden.

theprovocationpeople.com/2025/06/fighting-for-a-fair-and-free-future/.

June 28, 2019